IOFC: the link between sustainability and profitability

A “SUSTAINABLE” and “HIGH-PERFORMING” dairy farm:

two sides of the same COIN!

Often, in the recent past and sometimes even today, the idea has spread that a high-performing dairy farm cannot truly be sustainable and is usually large-scale, with cows that are not particularly fertile or long-lived, as they are “worn out” by the production process.

However, the reality that emerges from analysing the best-performing dairy farms reveals exactly the opposite.

The top farms show very high milk production together with fertile and long-lived cows, very few health issues and excellent economic results.

There is also no correlation between these outcomes and farm size, which may be small or very large. They are simply all extremely sustainable and high-performing.

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY A SUSTAINABLE FARM?

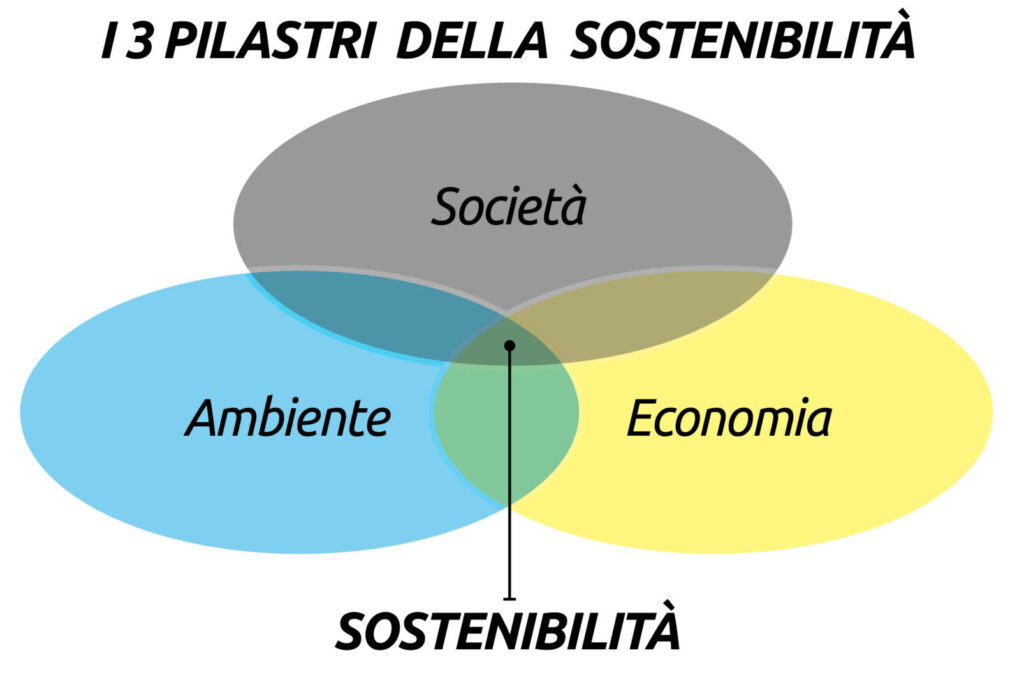

“Sustainability” is generally understood as the ability to meet present needs without compromising the ability to meet future needs, based on three pillars:

1) enviromental,

2) economic,

3) social

These dimensions must necessarily coexist for the development of any activity to be truly “sustainable” (see the Brundtland Report, 1987, WCED, Our Common Future).

A “sustainable dairy cow barn” is therefore a farming system that has a negligible or zero environmental impact, achieves strong economic profitability and enhances the social value of those who work within it. All these characteristics coincide with a high-performing dairy farm at every level—environmental, economic and social—making sustainability and performance different aspects of the same reality.

Sustainable dairy farming – environmental performance

With regard to the environmental aspect, a dairy farm is characterised by its impact in terms of:

– Agronomy (manure management, soil fertility, forage production, etc.);

– Emissions of potentially polluting substances (uch as greenhouse gases CO₂ and methane, ammonia), nitrates and phosphorus;

– Use of technical inputs, both nutritional and non-nutritional (reduced use of medicines, additives to improve efficiency or reduce methane emissions, technical devices such as next-generation collars to improve health and fertility, etc.).

In each of these areas, the management approach adopted can make the process sustainable or, conversely, produce the opposite effects. What is particularly interesting and important, however, is that the more management actions generate sustainability, the more technical and economic performance increases.

At the agronomic level, for example, optimal management of livestock effluents—providing for their application close to the vegetative phase of crops (so that fertilising elements, nitrogen in particular, are absorbed by plants without contaminating groundwater or being leached) and using methods that reduce or even prevent the loss of ammoniacal nitrogen to the atmosphere, such as direct soil injection or immediate incorporation—does not only produce significant environmental benefits in terms of sustainability. It also leads to substantial economic savings through reduced purchases of chemical fertilisers (which are costly and have a high carbon footprint), as well as a marked improvement in both the quantity and quality of forage production and in soil fertility (increased organic matter, improved soil structure and greater cation exchange capacity).

Slurry contains, on average, 4–5 kg of total nitrogen (N) per tonne. Therefore, incorporating approximately 60 tonnes of slurry per hectare on the same day as application can save up to 250 kg of nitrogen fertiliser compared to surface application without incorporation.

The stable organic nitrogen present in the faeces is gradually released into the soil, providing a steady supply of nutrients that become available to crops throughout the growing season. Approximately 40–50% of the stable organic nitrogen in manure is available in the first year, 12–15% in the second year, 5% in the third year and about 2% in each subsequent year.

The total nitrogen available from manure for plant growth derives from three sources:

Available N = (ammonium N from the current application) + (stable N mineralised from the current application) + (organic N mineralised from past applications).

With regard to emissions, the possibility of containing—almost effectively eliminating—the release of ammonia into the atmosphere, which is potentially harmful due to its role in the formation of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), has been mentioned above. Particulate matter (PM) refers to the mixture of airborne substances of varying sizes. These include fibres, carbonaceous particles, metals, silica, and liquid and solid pollutants that enter the atmosphere through natural processes or human activities.

Sustainable and high-performing dairy farming – economic performance

For a dairy farm, Gross Marketable Production (GMP), in a strictly livestock-related sense (excluding any associated activities such as biogas, photovoltaic systems or sales of agricultural products), is almost entirely generated by milk sales. Therefore, maximising saleable milk production while reducing production costs is the fundamental prerequisite for achieving maximum farm profitability.

When analysing the main cost centres in milk production, the first four—feeding of lactating cows, labour costs, replacement (heifer rearing) costs and depreciation—account for almost 90% of total costs. The most significant of these is feeding lactating cows, which alone represents approximately 50% of the total cost.

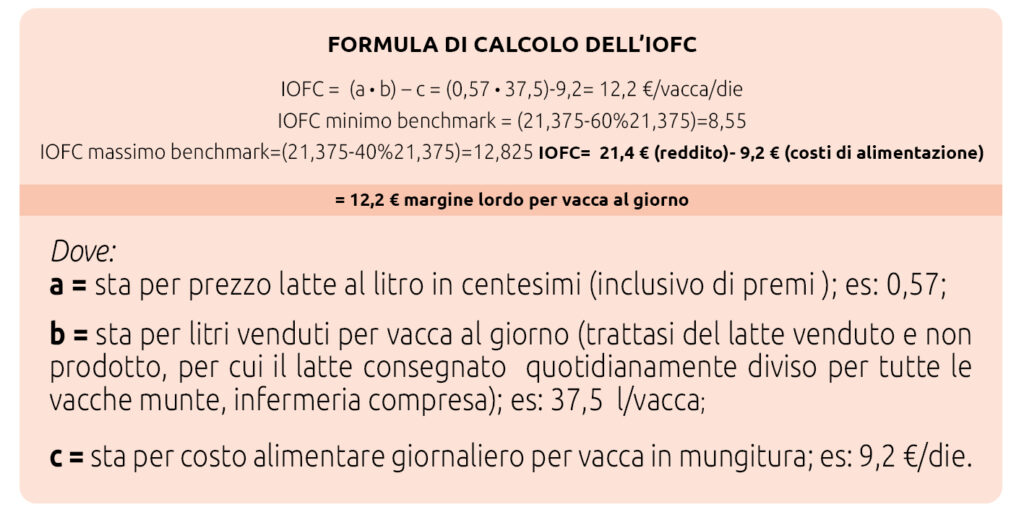

Given the substantial weight of feeding costs in the economics of milk production, it is natural to consider reducing feed costs (and rightly so). However, this objective must be pursued with intelligence and expertise, otherwise it becomes counterproductive—particularly if feed cost reduction leads to a loss of saleable milk greater than the savings achieved on feed. Precisely to assign an economic value to feeding decisions based on costs, the concept of IOFC (Income Over Feed Cost) was developed. IOFC decouples ration cost from its intrinsic value and instead highlights its economic return in terms of ROI.

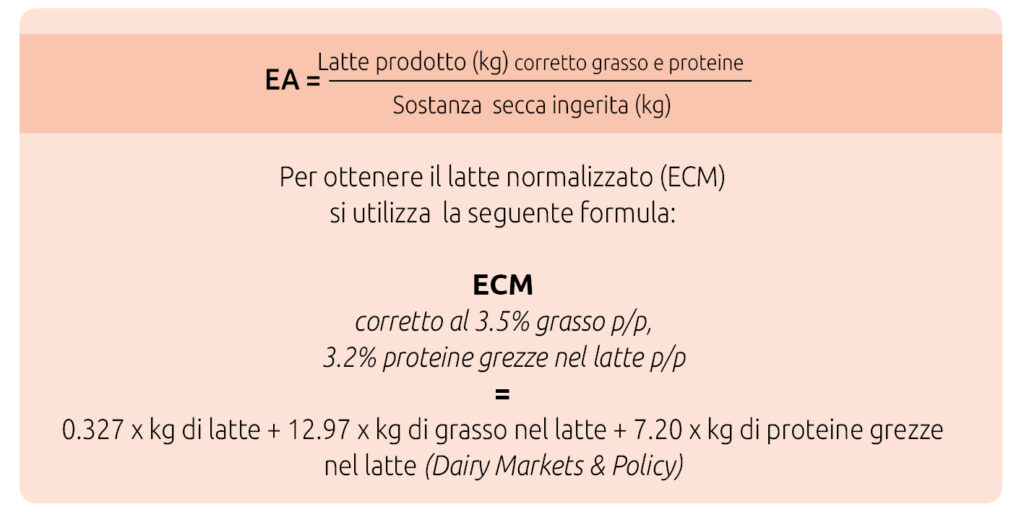

Using the smallest possible quantity of feed to produce the maximum amount of saleable milk is both an economic concept and one with strong sustainability implications, considering the carbon footprint associated with feed production.

Thus, the technical–economic parameter of Feed Efficiency (kg of fat- and protein-corrected milk produced per kg of dry matter intake) also becomes a key objective for true and direct sustainability.

This is because improving feed efficiency requires nutritionally and fermentatively balanced diets (which generate less ammonia and potentially less methane), fed to healthy cows (in excellent health, free from disease and oxidative or inflammatory states caused by poor welfare), and under optimal physiological and hormonal conditions to convert feed into milk…

These conditions coexist primarily in fresh cows. Therefore, for a dairy farm, it becomes essential to achieve excellent fertility at the beginning of lactation, combined with a significant proportion of mature, long-lived cows. These animals are better able to convert feed into milk, as they no longer require nutrients for growth and can distribute maintenance requirements over a higher feed intake due to their greater body weight.

Another major cost centre—often the third after labour, and sometimes even the second after feeding in terms of impact—is replacement cost. This represents, in economic terms, the number of heifers required to replace cows culled from the herd. As such, it is a key factor in the sustainability of dairy farming, as increases in replacement rates lead to a higher carbon footprint (greater feed consumption), increased methane production per kg of milk produced, and reduced feed efficiency.

All of this has a direct economic impact on the profitability of milk production. To measure the true profitability of milk produced—net of the improved technical efficiency resulting from high replacement rates—we have developed the concept of PSP (production per productive subject). PSP is calculated by dividing the milk sold in a given year by the sum of the lactating and dry cows present in that year, to which the number of cows culled (and therefore replaced to form the current milking herd) in the year considered and in the previous year is added (note: two years are considered because new heifers enter production at 24 months of age).

The PSP value should obviously be as high as possible, with desirable levels exceeding 7,000 kg of milk sold per head.

The higher the PSP value, the greater the sustainability and income of the farm.

Sustainable and high-performing dairy farming – social performance

Last, but not least, is the social dimension of a sustainable and high-performing dairy farm.

ublic acceptance of dairy farming in its productive, economic, environmental and social dimensions has changed significantly in recent years.

Perhaps one of the underlying reasons for this shift is the growing generational gap, whereby many people have never had real contact with livestock farming—not even through the experiences of parents or grandparents. This has given rise to an environmentalist and animal welfare sensitivity that is often anthropomorphic rather than naturalistic or zoological in nature. As a result, high-performing farming systems and highly professional farmers are sometimes perceived as unsustainable and disrespectful of animals and the environment.

However, since science and real-world evidence clearly demonstrate the opposite, it remains our fundamental responsibility to engage in informative and constructive dialogue with a broad public audience. This audience, often in good faith but lacking objective data, risks undermining the activity of dairy farms that are, in fact, highly virtuous in terms of sustainability and performance.

To stay up to date with all our latest news, follow us on Instagram or on Facebook.