Leaky Gut Syndrome or LGS

LEAKY GUT SYNDROME OR LGS

A challenge to overcome for the welfare, health and productivity of cows and calves.

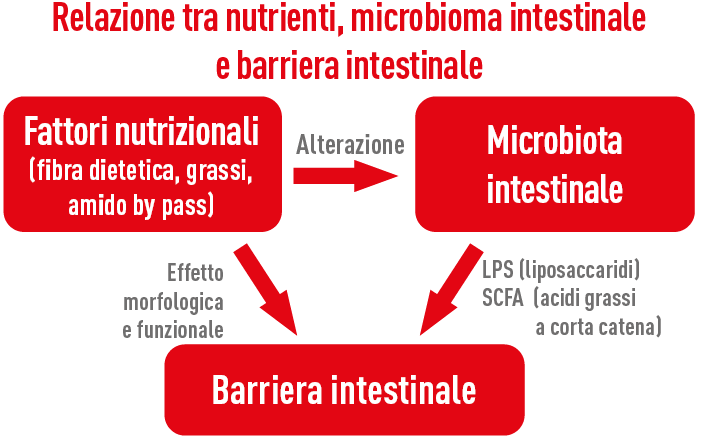

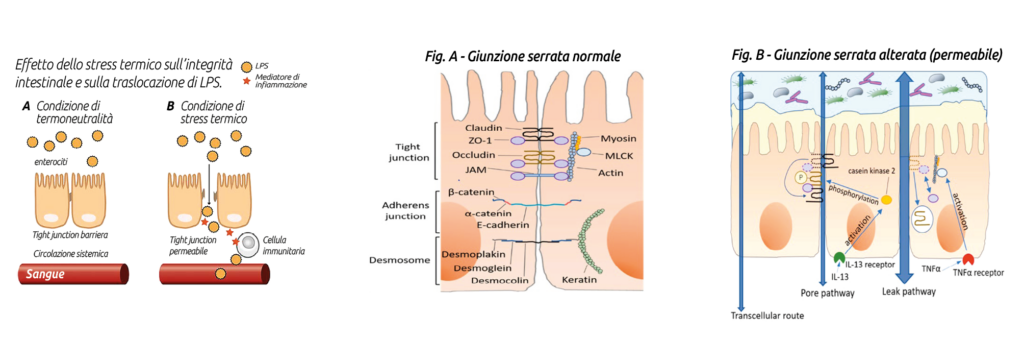

Leaky Gut Syndrome, or LGS, can be generally defined as the inability of the intestinal barrier to function as a semipermeable membrane, that is, to absorb the necessary nutrients and prevent undesirable substances (bacteria, LPS, feed antigens, etc.) from entering the bloodstream and the body.

In the presence of increased intestinal permeability, the possibility for undesirable substances to penetrate beyond the intestinal barrier due to alteration of tight junctions stimulates an immune response. This event is more likely to occur during the weaning phase of the calf and during the transition period of the cow.

What causes LGS?

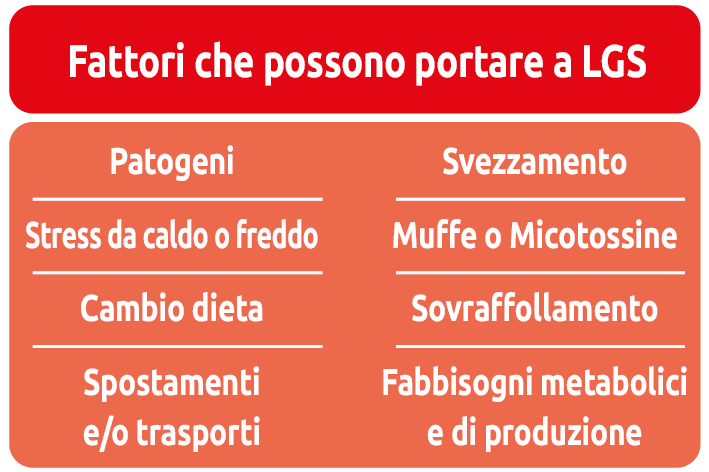

Several situations can lead to an increase in intestinal permeability through different mechanisms, but essentially all of them result in immune activation, which consistently leads to an increase in the inflammatory response, mainly triggered by the release of LPS (lipopolysaccharides contained in the cell membranes of Gram-negative bacteria). Among the various predisposing factors for Leaky Gut Syndrome we include heat stress (especially due to heat but also extreme cold), stress during the transition period, ruminal and intestinal acidosis, reduced feed intake, various environmental stresses (movements, transport, overcrowding, dietary changes, weaning, pathogens, molds and toxins, antibiotic treatments, etc.).

Heat stress and LGS

During heat stress, blood flow is redirected from the viscera toward peripheral tissues in an attempt to dissipate heat, resulting in hypoxia and nutrient deficits at the intestinal level, to which enterocytes are particularly sensitive. This leads to oxidative stress (Hall et al., 2001) and reduced ATP production, translating into functional and morphological alteration of tight junctions (Pearce et al., 2013).

All this results in increased permeability of the intestinal barrier, allowing the passage of LPS from the intestinal lumen into the portal and systemic circulation. These endotoxins have a high immune-activating power and are able to directly stimulate, or via GLP-1, insulin secretion (Kahles et al., 2014), even before triggering the inflammatory cascade, thus generating a metabolic picture of hyperinsulinemia (Baumgard and Rhoads, 2013).

This situation generates a severe metabolic energy deficit (consider that activation of the immune system consumes about 1 kg of glucose every 12 hours), with serious productive and health repercussions. Transition period and LGS

Transition period and LGS

During the transition period, an increase in intestinal permeability, in addition to the possible presence of endotoxins of uterine or mammary origin (Mani et al., 2012), may also derive from conditions of ruminal acidosis, reduced feed intake, or other psychological stresses due to movement or competition. In any case, a moderate inflammatory state is physiologically inherent to the calving event.

The inflammatory state accompanying calving in the cow effectively reshapes the physiological nutrient partitioning, compromising normal productivity (Bertoni et al., 2008), as confirmed by experiments with TNFα infusion showing reduced production with increased TAG without increased NEFA. Indeed, in ketotic cows without other periparturient diseases (neither metritis nor mastitis), an increase in inflammatory markers such as LBP (lipopolysaccharide binding protein), serum amyloid A and haptoglobin is normally detected (Abuajamieh et al., 2016).

It should be remembered, however, that a moderate inflammatory state is “physiological” at calving and is necessarily useful for the normal postpartum evolutionary process, and only persistent and excessive inflammation should be avoided (Trevisi and Minuti, 2018). Therefore, the objective during this phase must be to regulate the “physiological” inflammatory process without suppressing it, as suppression could lead to worsening of cow health.

Ruminal and/or intestinal acidosis and LGS

Damage to the epithelium of the ruminal wall and the intestinal mucosa occurring during acidosis underlies the mechanisms leading to LGS in such situations. The condition producing acidosis derives from an accumulation of VFA relative to local absorption capacity at the ruminal or intestinal level, consequent to a sudden increase in fermentable starchy substrates. This situation follows an abrupt dietary change, as occurs in the calf during weaning or in the cow at calving, or when there is an excess of intestinal starch bypass.

The latter event occurs in conjunction with excessive quantitative starch intake, starch poorly degradable in the rumen, or alterations in digesta transit exceeding pancreatic amylase digestive capacity (which in the cow is probably limited to a maximum of 1 kg of bypass starch), leading to fermentation in the large intestine with consequent local acidosis and possible translocation of LPS from the intestinal lumen into the bloodstream, thus causing the onset of LGS and its related consequences (Li et al., 2012; Minuti et al., 2014).

Reduced feed intake and LGS

All conditions that result in feed intake restriction (heat stress, weaning, competition due to movement or overcrowding, transport) generate stress that produces intestinal hyperpermeability (Chen et al., 2015). A recent trial with cows fed at 40% compared to cows fed ad libitum showed a reduction in ileal villus length and crypt depth (Kvidera et al., 2017).

Recent studies indicate that under feed restriction, CRF (corticotropin-releasing factor) may be the mechanism leading to LGS (Wallon et al., 2008; Vanuytsel et al., 2014). Indeed, CRF and other related factors such as urocortins 1, 2 and 3 and their G-protein-coupled receptors CRF1 and CRF2, following feed restriction, have been identified as the main mediators of intestinal stress, causing inflammation, altered motility and permeability, and also inversion between secretion and absorption of ions, water and mucus (Rodiño-Janeiro et al., 2015).

This alteration appears to be largely regulated by intestinal mast cells (Santos et al., 2000); these cells are important mediators of both innate and adaptive immunity and express CRF1 and CRF2 receptors, which may partly explain the association between stress and intestinal hyperpermeability (Smith et al., 2010; Ayyadurai et al., 2017).

Moreover, mast cells synthesize various pro-inflammatory mediators (such as IFN-γ and TNF-α) that are released upon activation, mainly during degranulation (Punder and Pruimboom, 2015). Excessive mast cell degranulation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of many intestinal disorders (Santos et al., 2000).

Pathophysiological consequences of leaky gut

Translocation of LPS following increased intestinal permeability in LGS leads to activation of immune cells and consequent inflammation, whose high energy cost redirects nutrients away from normal anabolic processes for milk and muscle synthesis, thereby compromising productivity.

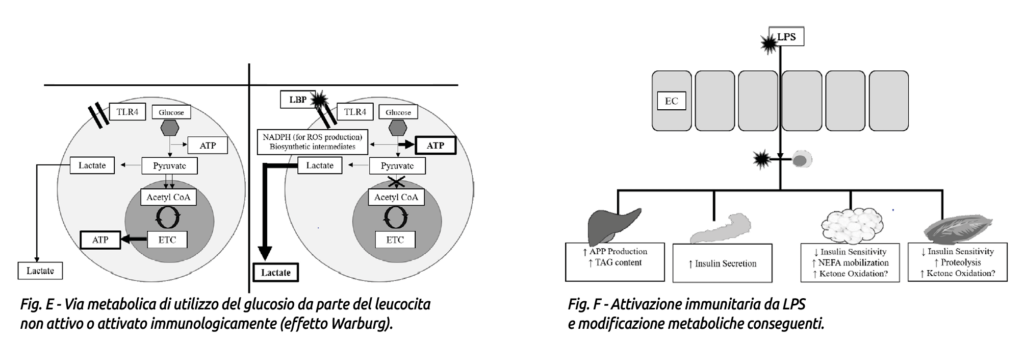

Activated immune cells begin to use glucose through aerobic glycolysis rather than oxidative phosphorylation, a process known as the Warburg effect (Fig. E). This metabolic switch allows rapid ATP production and synthesis of metabolic intermediates that support cell proliferation and ROS (reactive oxygen species) production (Calder et al., 2007; Palsson-McDermott and O’Neill, 2013).

To facilitate glucose uptake, immune cells become more insulin-sensitive and increase expression of GLUT3 and GLUT4 transporters (Maratou et al., 2007; O’Boyle et al., 2012), while peripheral tissues become insulin-resistant (Poggi et al., 2007; Liang et al., 2013).

Furthermore, metabolic adaptation to LGS, involving hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia (depending on stage and severity of the LPS stimulus), increases insulin or glucagon levels, muscle amino acid metabolism and consequent nitrogen losses (Wannemacher et al., 1980). A state of hypertriglyceridemia also occurs (Filkins, 1978; Wannemacher et al., 1980; Lanza-Jacoby et al., 1998; McGuinness, 2005).

Interestingly, despite the presence of hypertriglyceridemia, blood levels of beta-hydroxybutyrate often decrease following LPS administration (Waldron et al., 2003a, b; Graugnard et al., 2013; Kvidera et al., 2017a). The mechanism leading to LPS-induced reduction of beta-hydroxybutyrate is not yet fully understood but may be explained by increased oxidation of ketone bodies by peripheral tissues (Zarrin et al., 2014). See Fig. F.

Overall, these metabolic adaptations following LPS-induced immune activation are presumably implemented to ensure adequate glucose availability for activated leukocytes.

How to limit the onset of LGS?

Strategies to limit the onset of leaky gut syndrome must simultaneously aim to:

reduce LPS (lipopolysaccharide) production;

limit morphological and functional damage to tight junctions.

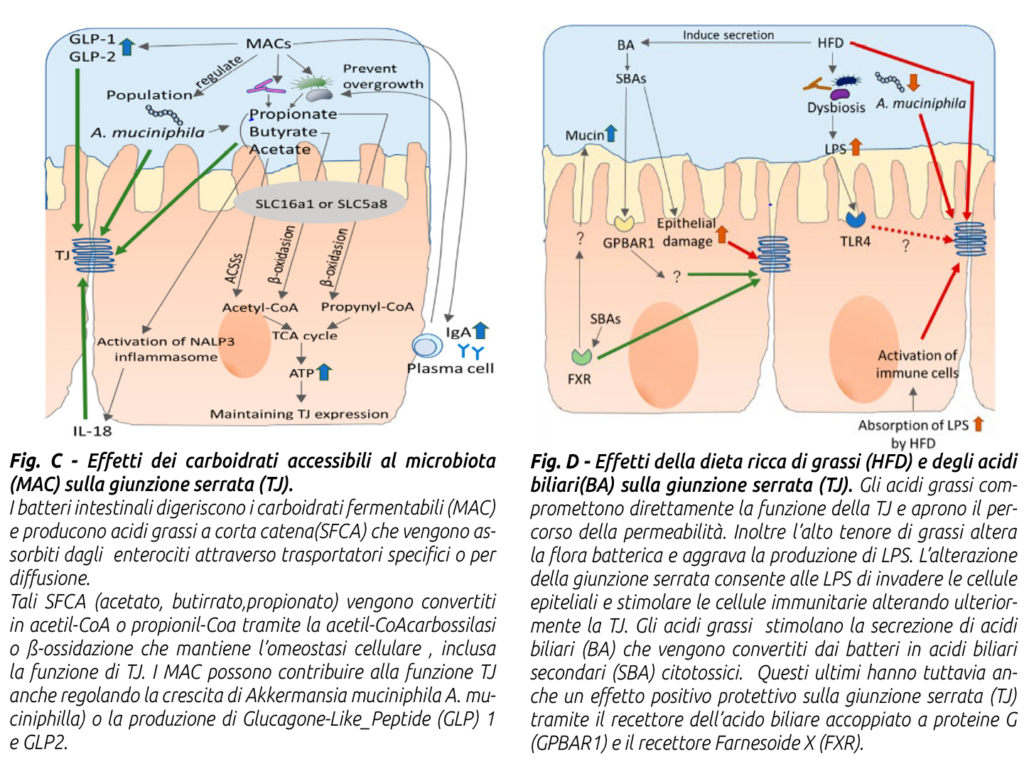

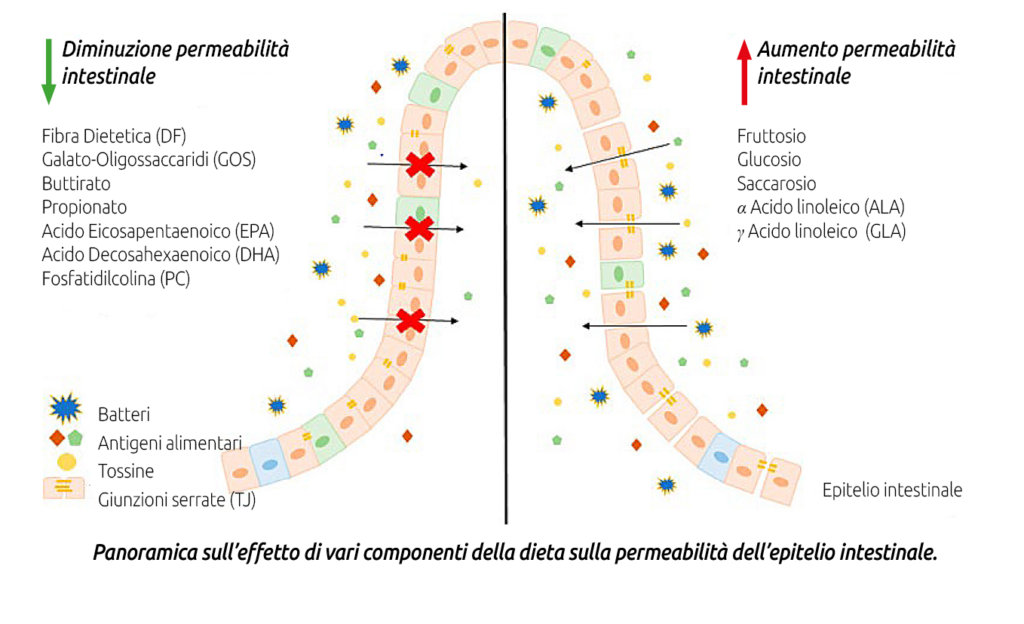

To reduce LPS production, it is necessary to limit conditions that cause intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and favor Gram-negative bacteria, whose lysis releases LPS. This can be achieved by using balanced diets with:

a) correct fiber supply in quantity and quality;

b) non-excessive intake of fermentable carbohydrates at the intestinal level, especially bypass starch;

c) controlled intake of free fatty acids (from oils or whole seeds rich in lipids, especially if finely ground or extruded) at the ruminal and intestinal level (for example, excessive amounts of an essential fatty acid such as linoleic acid Ω6, if not balanced with linolenic acid Ω3, exert a dysbiotic and pro-inflammatory action on the intestinal microbiota);

d) supplementation with nutraceutical additives regulating the ruminal-intestinal microbiota such as live yeasts, mannan-oligosaccharides, bypass organic acids (Agecon Tecnozoo®).

On the other front, the risk of leaky gut syndrome can be limited by reducing morpho-functional damage to tight junctions by ensuring:

a) conditions for maximum feed intake;

b) avoidance of heat stress situations;

c) avoidance of ruminal and intestinal acidosis;

d)avoidance, as much ad possible, of general stress situations (movements, handling, etc.);

e) supply of epithelial-protective dietary factors, particulary protected zinc (chelated or proteinated forms) and vitamis A and E.

IN CONCLUSION, we can certainly state that reducing and preventing leaky gut syndrome is not only possible but absolutely necessary if we want to ensure maximum welfare and health for our cows, and full productivity and profitability for ourselves.

AGECON RBT

Mineral complementary feed for dairy cows

- With brewer’s yeast lysate, which increases ration digestibility;

- Optimizes feed quality by increasing yields;

- Absorbed formic and propionic acids.

Source: Ex Dairy Press, article by Dr. Pierantonio Boldrin, Veterinary Surgeon, Head of the Technical Service, Tecnozoo.

For more information, call +39 049 9350 700 or email tecnozoo@tecnozoo.it

To stay up to date with all our latest news, follow us Instagram or on Facebook.