Calf intestinal microbiome and microbiota

A synergistic effect for gastrointestinal system well-being

Despite preventive measures, enteric infections in neonatal calves remain one of the leading causes of calf mortality. With new regulations limiting the prophylactic use of antimicrobials, there is an urgent need for alternative approaches to minimize the incidence of diarrhea in neonatal calves.

Methods are required to improve calf intestinal condition during the pre-weaning period in order to reduce susceptibility to enteric infections. Manipulation of the intestinal microbiome is a key factor influencing intestinal function.

Calf intestinal microbiome and microbiota – Definitions

Progression of cellular differentiation and growth during the first weeks of life of a cereal-fed dairy calf

(The progression is from 3 to 35 days of age; the upper row from left to right, the lower row from left to right).

The terms microbiota and microbiome refer to a heterogeneous population of microscopic organisms residing in a defined space at a given time. The microbiota includes microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, archaea, protozoa, and viruses that live and colonize a specific environment.

The microbiome, on the other hand, is defined as the genetic heritage of the microbiota, namely the total set of genes expressed by these microorganisms. The total number of microbiota genes is estimated to be approximately 100 times greater than that of the human genome, and the microbial genome shares about 99% of its genes with the human genome. Microbiota and microbiome are therefore distinct but closely related concepts.

Changes in the microbiota lead to changes in the microbiome, impacting body homeostasis. The microbiota can be divided into bacteriota (bacterial component), virota (viral component), and mycota (fungal component). In common usage, the term microbiota generally refers to the bacterial fraction, due to the greater ability of bacteria to metabolize digestion products through carbohydrate and protein fermentation, producing fatty acids, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, ammonia, amines, phenols, and energy.

The intestinal microbiome plays a crucial role in the development, maturation, and homeostasis of the mucosal immune system. Dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiome has been linked to various enteric disorders that cause intestinal tissue inflammation. Maintaining normal bacterial density and composition is essential for a healthy intestine.

A true symbiosis exists between intestinal mucosal epithelial cells and bacteria through specific epithelial membrane receptors capable of recognizing the microbiome. The mucosal immune system can influence microbiome changes and vice versa.

Pre-weaned calf intestinal microbiome: what do we know?

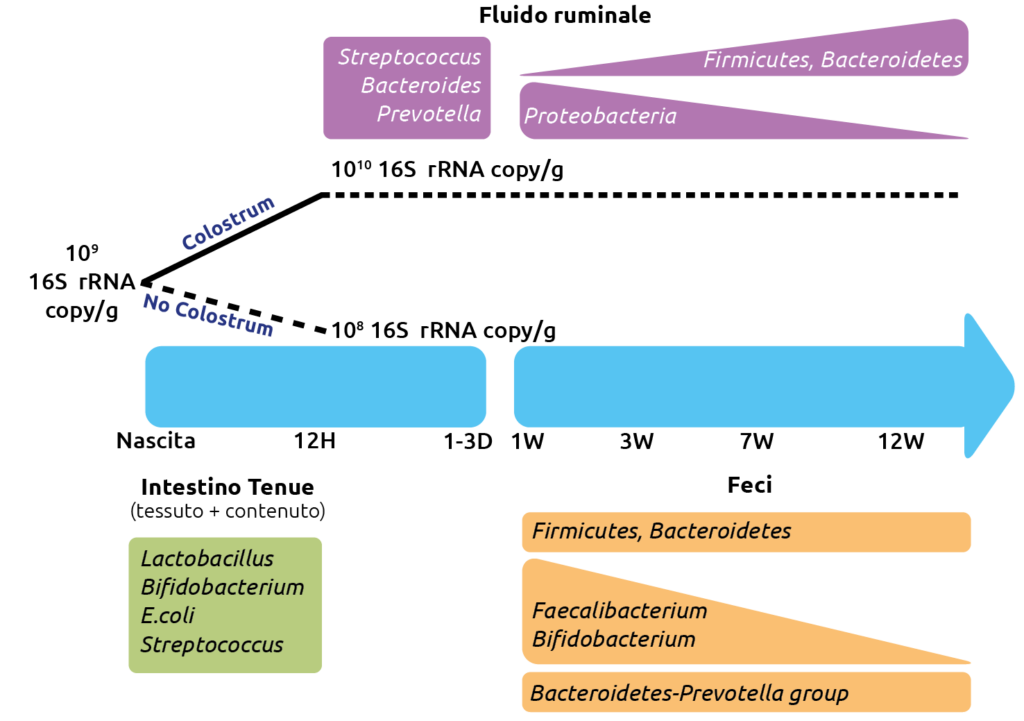

The calf intestinal microbiome is already present in the fetus and, therefore, in the meconium, and it changes with advancing age and according to diet. Recent studies have reported the presence of a diversified microbiota in calf fetuses aged between 5 and 7 months, suggesting that colonization of the bovine intestine by so-called “pioneer” microbiota may begin as early as mid-gestation.

It has also been demonstrated that maternal nutritional management and prenatal supplementation with vitamins and trace elements induce changes in the uterine microbial community that can influence colonization of the intestine, vagina, and ocular surface of calves.

Finally, the calf intestinal microbiota varies according to animal genetics and depending on the intestinal tract segment.

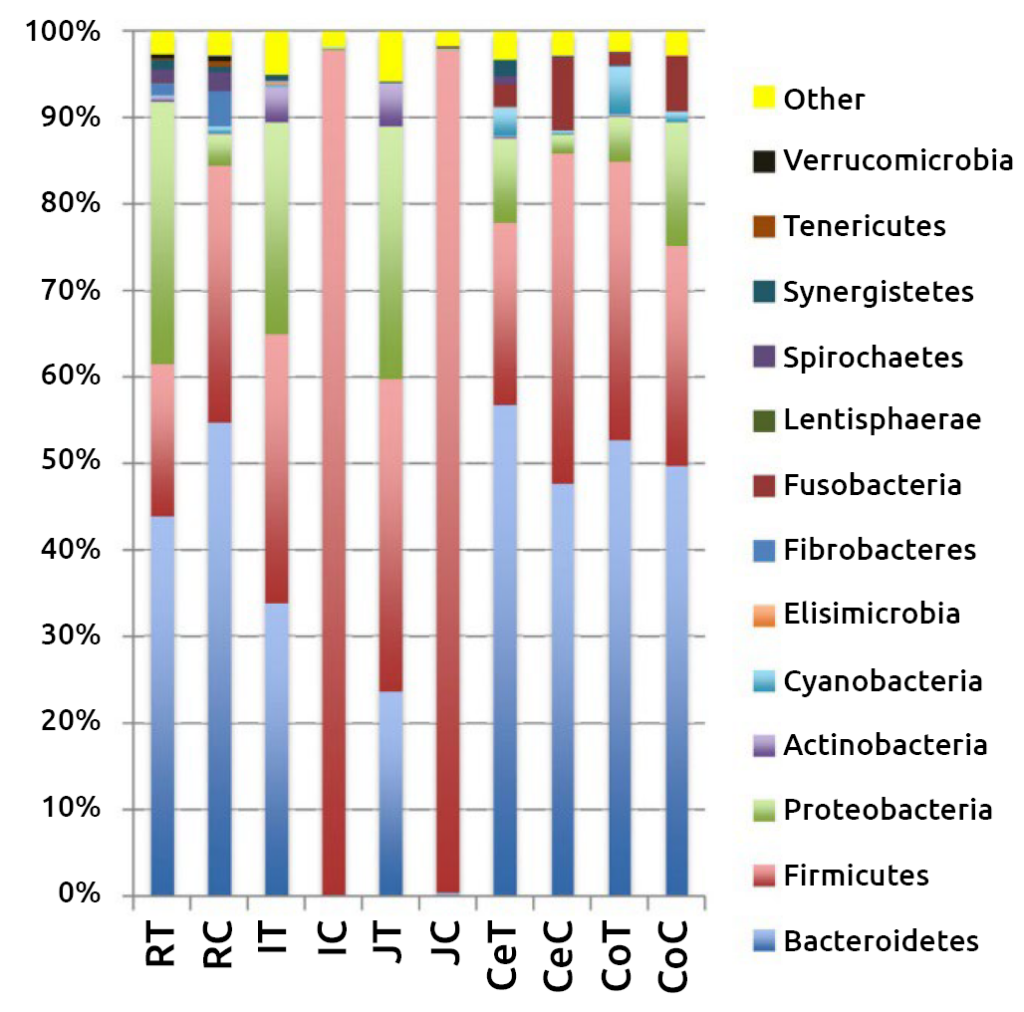

Composition of intestinal bacterial phyla at different levels, both in the mucosa and in the digesta, throughout the gastrointestinal tract of dairy calves. RT, ruminal tissue; RC, ruminal content; JT, jejunal tissue; JC, jejunal content; IT, ileal tissue; IC, ileal content; CeT, cecal tissue; CeC, cecal content; CoT, colonic tissue; CoC, colonic content.

Nilusha Malmuthuge et al., ASM Journals.

The importance of the first week

Initial colonizers (Streptococcus and Enterococcus) utilize available oxygen in the intestine and create the anaerobic environment required by strictly anaerobic intestinal residents such as Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides. The presence of Bacteroides in the intestine plays a vital role in the development of immunological tolerance to commensal microbiota, while the composition of Bifidobacterium in the intestine is associated with a reduced incidence of allergies. Therefore, neonatal intestinal colonization represents a critical period for the development of the intestine and the naïve immune system and may have long-term effects on health.

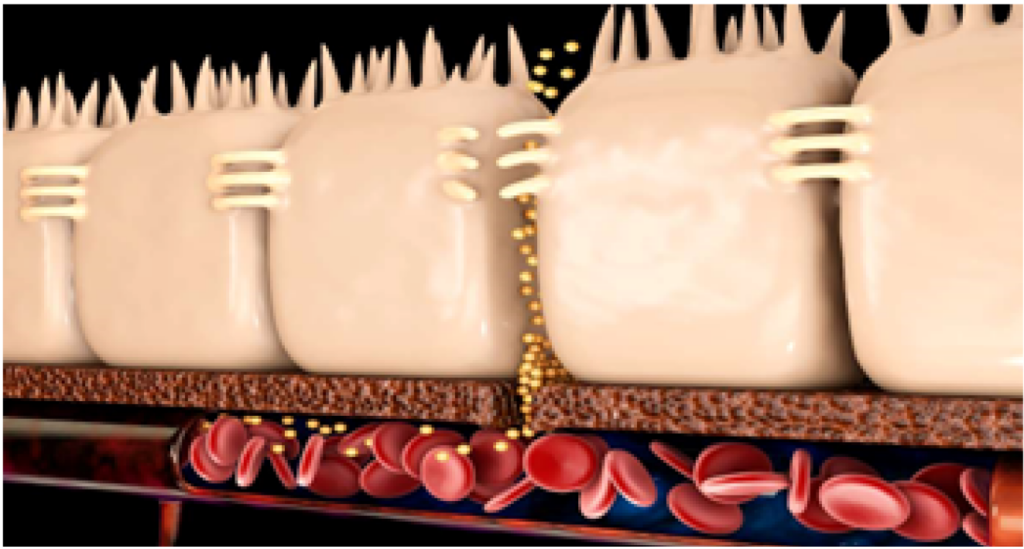

Early studies on preruminant intestinal bacterial colonization focused mainly on pathogenic Escherichia coli in calves and described the pathogenesis of neonatal diarrhea. Microscopic observations revealed that pathogenic E. coli preferentially attaches to and damages the mucosal epithelium of the ileum and large intestine, but not the duodenum and jejunum of neonatal calves.

Microscopic imaging revealed that pathogenic E. coli preferentially attaches to and effaces the mucosal epithelium of the ileum and the large intestine, but not of the duodenum and jejunum in neonatal calves.

Administration of probiotic strains isolated from the calf intestine has reduced enteric colonization by pathogenic E. coli O157:H7 in pre-weaned calves. Similarly, supplementation of neonatal calves with Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus during the first week of life improved weight gain and feed conversion while reducing the incidence of diarrhea.

When solid feed intake begins, the intestinal microbiome changes, and abrupt dietary transitions may increase intestinal permeability through tight junctions. Increased permeability allows bacteria or bacterial products from the intestinal lumen to enter mucosal tissue, potentially stimulating host immune responses and leading to pathology.

These effects are more pronounced in pre-weaned calves than in weaned calves, suggesting that probiotic supplements are more effective while the intestinal microbiota is still establishing and less effective once the microbiome has stabilized. Administration of Lactobacillus to young calves increases total serum immunoglobulin G concentration, providing evidence of host–microbiome interactions that can influence calf condition (Al-Saiady, J. Anim. Vet. Adv., 2010).

More recently, supplementation of neonatal calves with prebiotics (galacto-oligosaccharides) has been associated with increased abundance of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in the colon of 2-week-old calves (Marquez CJ, University of Illinois, 2014). However, this effect was less pronounced in 4-week-old calves, again suggesting that microbiome manipulation is more effective during the early colonization period.

Antimicrobial use at weaning and intestinal microbial composition

Altering the balance of the calf intestinal microbiota means shifting from a state of eubiosis to one of disorder or dysbiosis. Antimicrobials cause dysbiosis in the intestinal tract of pre-weaned calves. Feeding waste milk containing antimicrobial residues (e.g., β-lactams, enrofloxacin, florfenicol, streptomycin) increases the presence of resistance genes in Escherichia coli populations compared with calves fed milk replacers free of residues. This results in reduced antimicrobial effectiveness when treatments are required for infectious diseases.

Mucosal immune system in calves

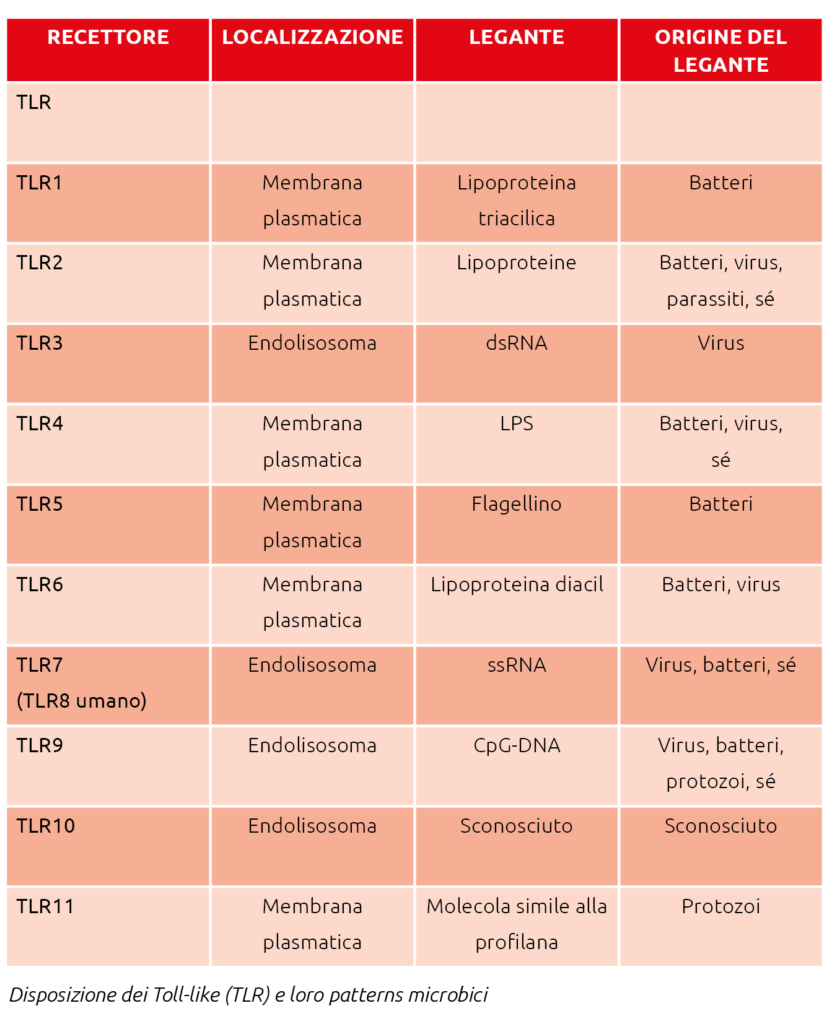

The mucosal immune system includes physical barriers (mucus layer, epithelium), chemical barriers (antimicrobial peptides, secretory IgA), pattern-recognition receptors (Toll-like receptors, NOD-like receptors), and a repertoire of cellular immune defenses (innate and adaptive).

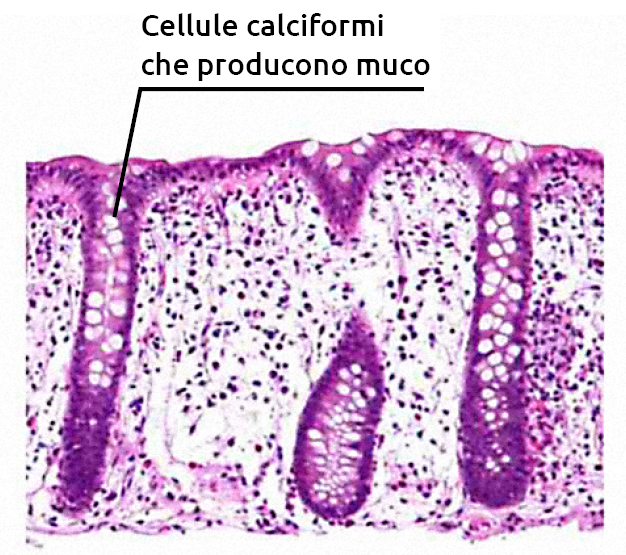

The mucus layer, the first secreted physical barrier, contains glycosylated mucins forming a mesh that traps microbiota. Secretory compounds (IgA, antimicrobial peptides) regulate microbiota growth on the mucus layer. Beneath the mucus layer, a single layer of epithelial cells connected by intracellular junctional complexes (tight junctions) regulates macromolecule movement across the epithelium. The calf intestinal microbiota is essential for intestinal mucus secretion, a key physical barrier throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

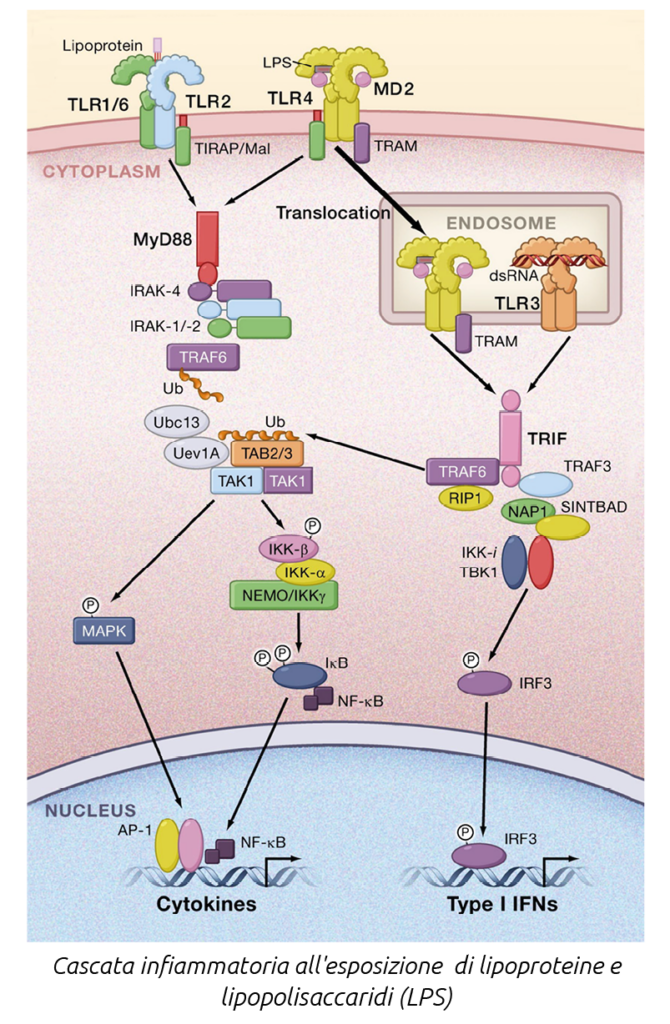

Initial infection perception is mediated by pattern-recognition receptors that detect specific molecules and trigger downstream responses.

These include Toll-like, RIG-I-like, NOD-like, and C-type lectin receptors. Toll-like receptors play a crucial role in host defense against microbial infections. The microbial patterns recognized by TLRs are not exclusive to pathogens but are also produced by commensals. Inflammatory responses to commensal bacteria are thought to be avoided through recognition of specific molecular patterns such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and lipoteichoic acid (LTA). TLRs act as sensors of microbial infection and are essential for initiating inflammatory and immune defense responses.

Experts recommend

Dietomilk

Milk replacer for use in cases of enteric disorders

- Action on fecal consistency

- Nutritive support;

- Components with rehydrating action.

Bireidral 1+2

Saline–energy rehydration product for calves, supporting a balanced start in fatigued or debilitated animals and as an aid in cases of digestive disorders.

To stay up to date with all our latest news, follow us on Instagram or on Facebook.