Hypocalcemia at calving in dairy cows

Physiological if mild and transient

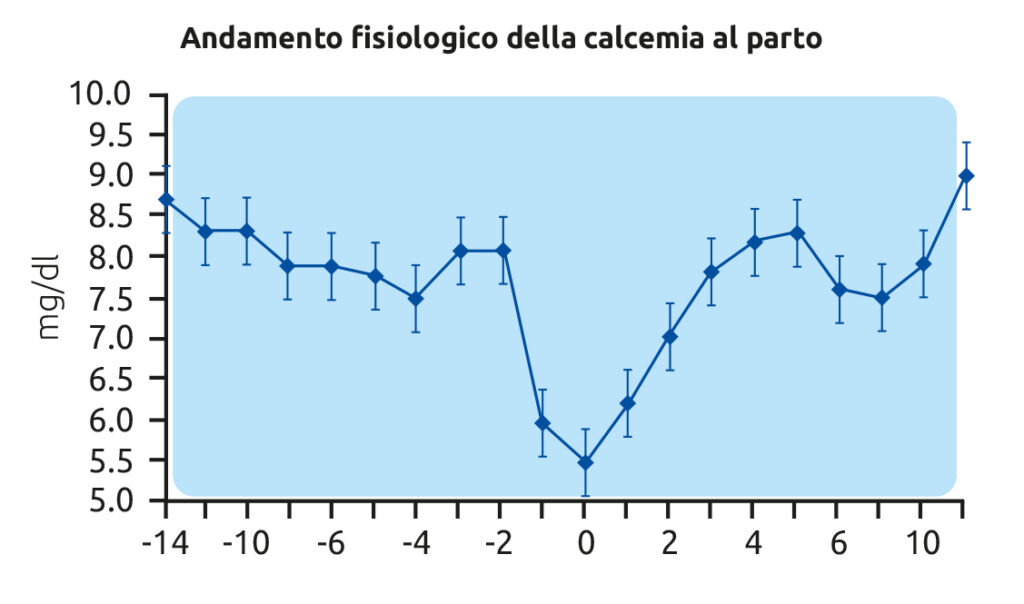

At calving, the large and sudden demand for calcium associated with the expulsive phase, together with the marked calcium outflow due to colostrum production, leads—even under optimal conditions—to a normal reduction in blood calcium levels in the cow. This condition remains within the physiological range if the decrease is limited and transient, and if the cow is able to rapidly restore normal calcemia.

What blood calcium values can be expected at calving?

Within the first 48–72 hours after calving, proper functioning of the homeostatic system regulating calcemia restores blood calcium levels—initially reduced to around 6 mg/dL immediately after calving—back to physiological values of 8.0–8.5 mg/dL.

This occurs when the parathyroid hormone (PTH) – activated vitamin D₃ system (calcitriol or 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol) functions optimally, which requires the following three conditions:

1) Proper responsiveness of PTH receptors;

2) Complete hydroxylation of vitamin D, enabling its hormonal activity;

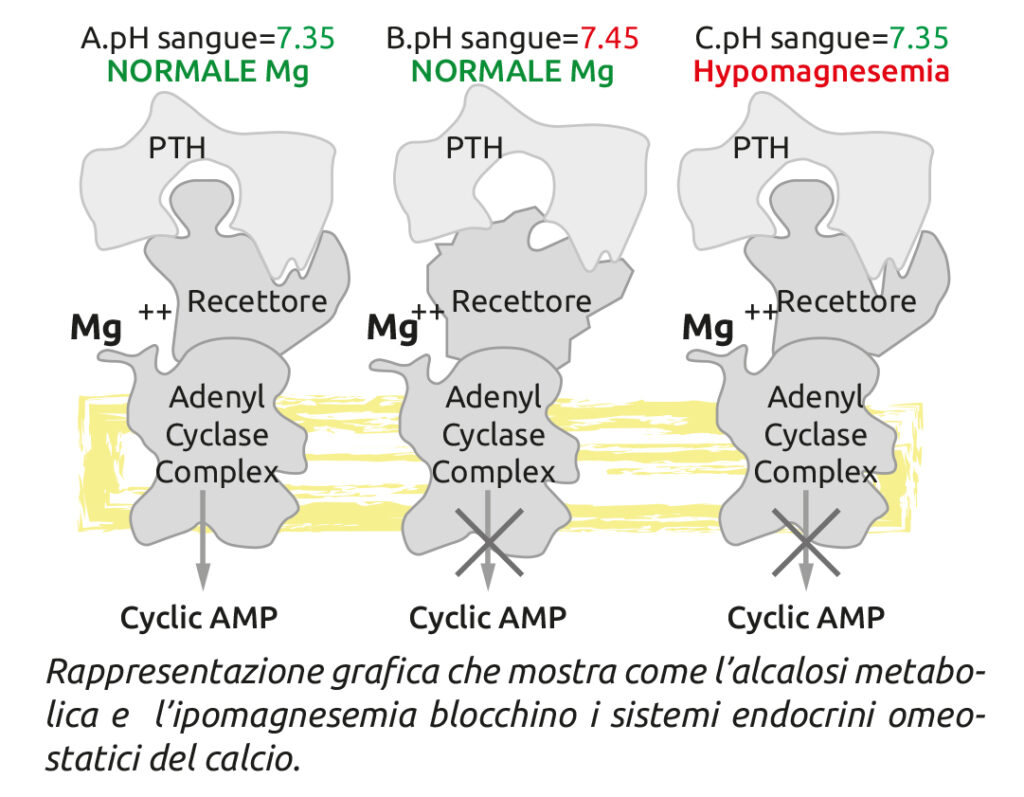

3) Activation of the adenylate cyclase complex (cyclic AMP–G protein), which is magnesium (Mg) dependent.

How to optimally manage calcemia at calving?

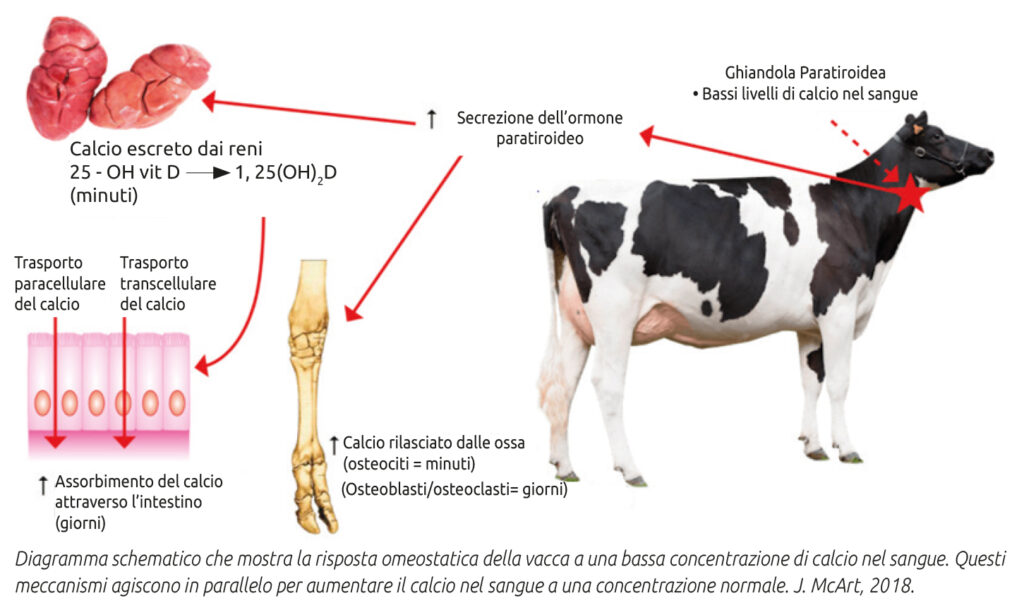

The parathyroid gland responds rapidly to declining blood calcium levels by producing PTH. Acting on specific cells in bone, kidney, and intestine, PTH promotes an increase in serum calcium concentration. Specifically, PTH stimulates:

1) Bone level: demineralization and release of calcium and phosphorus through osteoclast activation;

2) Renal level: calcium reabsorption and phosphorus excretion;

3) Intestinal level: increased calcium absorption.

These effects of PTH, together with those of vitamin D₃, occur only if PTH receptors are correctly configured—a condition ensured by physiological blood pH and impaired under metabolic alkalosis.

Likewise, full hepatic efficiency is essential for vitamin D hydroxylation and activation. Adequate magnesemia is also critical, as magnesium is involved both in adenylate cyclase activation and in the synthesis of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol.

This highlights the importance of monitoring the mineral profile of the transition cow diet, with particular attention to potassium (K) and magnesium (Mg) levels, in order to achieve a DCAD close to neutrality (thus avoiding alkalosis) and to ensure appropriate Mg availability relative to K, given their direct competition for absorption at the ruminal level.

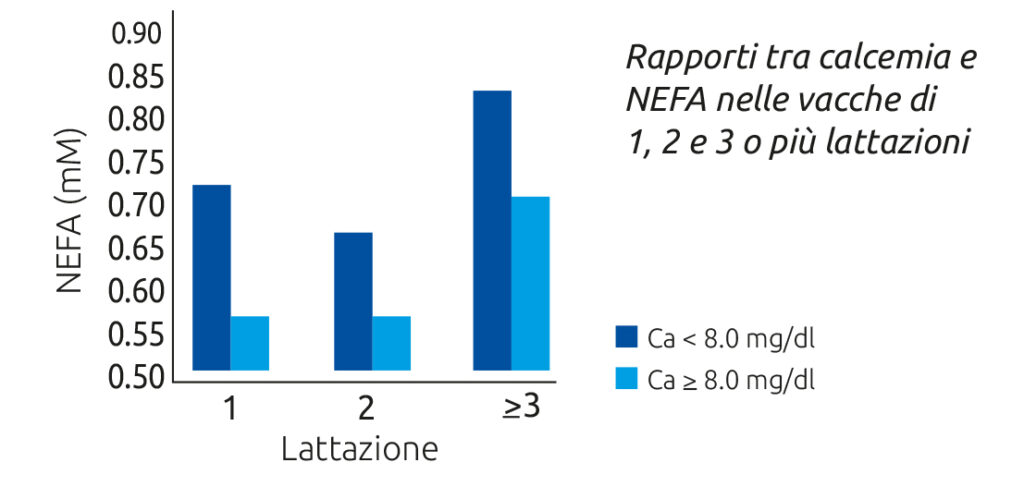

Equally important is preserving optimal liver function during the transition period, since hepatic hydroxylation activates vitamin D in its endocrine form. This can be supported through the use of lipotropic and hepatoprotective factors (such as choline, methionine, and carnitine). Notably, a close correlation exists between blood calcium levels and NEFA concentrations.

Calcium supplementation at calving: why, how, which form, and how much?

As noted, even under optimal conditions, calving induces a transient, physiological hypocalcemia, which homeostatic mechanisms attempt to counteract.

Calcium administration at calving is therefore extremely useful in supporting the body’s homeostatic mechanisms to achieve a rapid restoration of normal blood calcium levels.

Excluding cases of severe clinical hypocalcemia—where extremely low blood calcium levels require intravenous administration—oral supplementation is not only advisable but preferable in subclinical hypocalcemia. Oral administration avoids the risk of transient iatrogenic hypercalcemia, which is metabolically stressful and may pose cardiac risks. Furthermore, oral supplementation provides more stable post-absorptive blood calcium levels over time and integrates better with endogenous calcium homeostasis.

Passive calcium absorption—unlike active absorption—does not require vitamin D₃ and relies on the concentration gradient between intestinal lumen and blood. This gradient is achieved only with highly soluble and bioavailable calcium sources, which are therefore recommended for supplementation. Examples include calcium chloride or sulfate, organic sources such as calcium acetate or lactate, or calcium pidolate (highly effective, though more costly).

In contrast, calcium carbonate, despite being inexpensive and more palatable than calcium chloride, is poorly soluble and therefore unsuitable for oral supplementation aimed at rapid calcium absorption.

The recommended amount of calcium to be supplemented—using highly soluble and available sources—is approximately 100 g of elemental calcium. Provided solubility is not compromised, the form of administration (bolus, gel, liquid) does not significantly affect treatment efficacy.

That said, liquid formulations are generally more economical, highly effective, and carry minimal risk of ab ingestis. Any potential risk associated with liquid administration is effectively eliminated when delivered via drench using a pump.

In conclusion, oral calcium supplementation at calving:

1) Supports and enhances rapid restoration of calcemia in all cows via endogenous homeostatic mechanisms;

2) Addresses subclinical hypocalcemia, which affects approximately 50% of multiparous and 25% of primiparous cows—prompt treatment helps prevent more severe pathological outcomes (e.g., displacement, metritis, mastitis);

3) Represents a highly cost-effective intervention, with an estimated ROI of at least 1:4, considering the prevalence of hypocalcemia and the fact that a single case can result in losses of at least €250.

Let us therefore allow our cows to start the “lactation match” with a proper calcium kick-off.

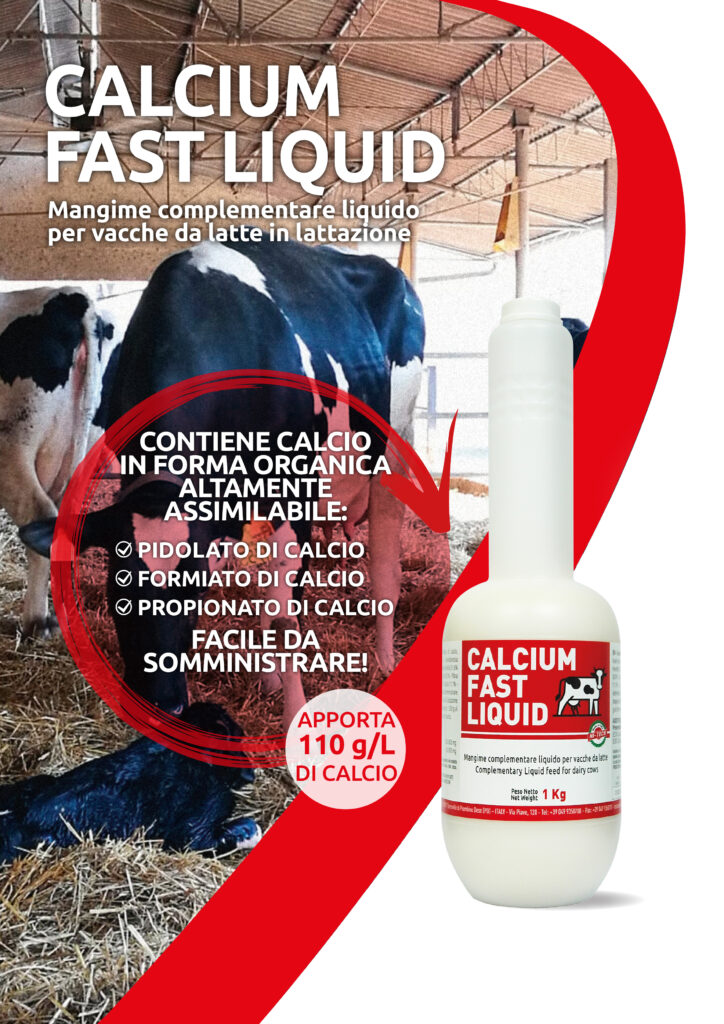

Discover Calcium Fast Liquid.

To stay up to date with all our latest news, follow us on Instagram or on Facebook.