Calf rumen development

From monogastric to polygastric

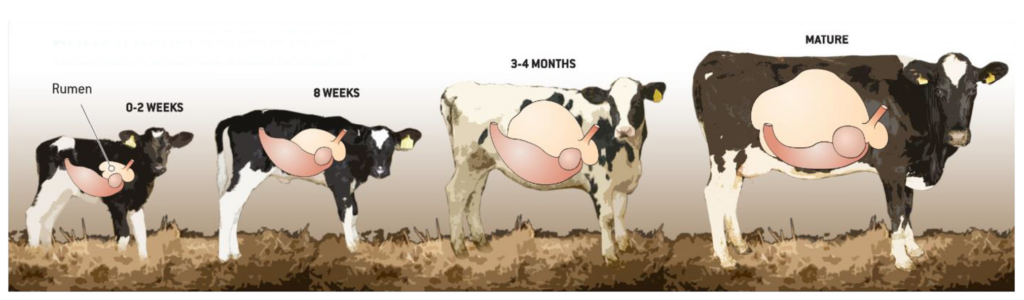

Development of the digestive tract in calves follows a uniquely organized system. In particular, thanks to the rumen and its colonization by microorganisms, the calf physiologically transitions from a pseudo-monogastric animal to a fully functional ruminant.

The progression of rumen development in calves can directly influence feed intake, nutrient digestibility, and overall growth. Even small changes in early feeding strategies and nutrition can markedly affect this process, with long-term consequences for growth, overall performance, and milk production in adult cattle.

Rumen development in newborn calves is therefore one of the most important and interesting areas of calf nutrition.

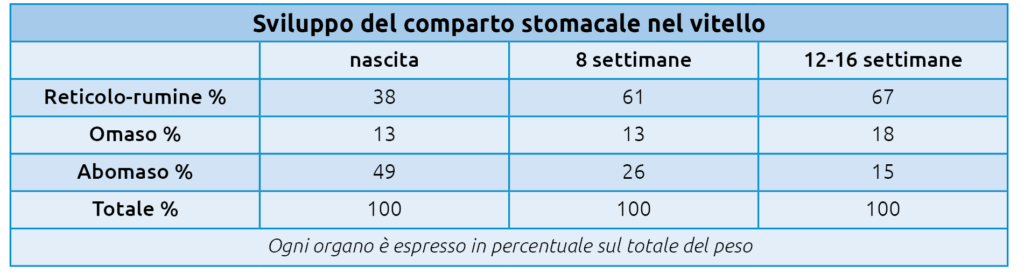

At birth, the abomasum is the only fully developed and functional stomach compartment and represents the most important digestive organ for the newborn calf. Digestion of fats, carbohydrates, and proteins relies mainly on digestive enzymes secreted by the abomasum and the small intestine, which function similarly to the digestive system of monogastric animals. Over time, as solid feed intake increases, the rumen begins to develop and progressively assumes a more significant digestive role.

Why is it important to know that the rumen is not developed during the first phase of life?

To avoid introducing hay too early.

Early hay feeding can lead to the formation of compacted “hay balls” within the rumen–intestinal tract, which occupy space without contributing to fermentation. This reduces concentrate intake capacity and slows rumen development.

Guide to rumen development

Establishment of the ruminal microbiota

At birth, the gastrointestinal tract of young ruminants is sterile. During the first hours of life, the forestomachs are rapidly colonized by a large microbial population.

Neonates acquire bacteria from the dam, pen mates, feed, housing, and the environment. Within one day of age, a high bacterial concentration—mainly aerobic or oxygen-utilizing bacteria—can already be detected.

Subsequently, although the total number of bacteria per milliliter of rumen fluid does not change dramatically, their composition does. As calves begin to consume dry feed, the microbial population shifts from predominantly aerobic to anaerobic and facultative anaerobic species, which progressively increase the production of fermentation end products. Among these, volatile fatty acids (VFA)—propionate, butyrate, and acetate—are of particular importance for rumen development.

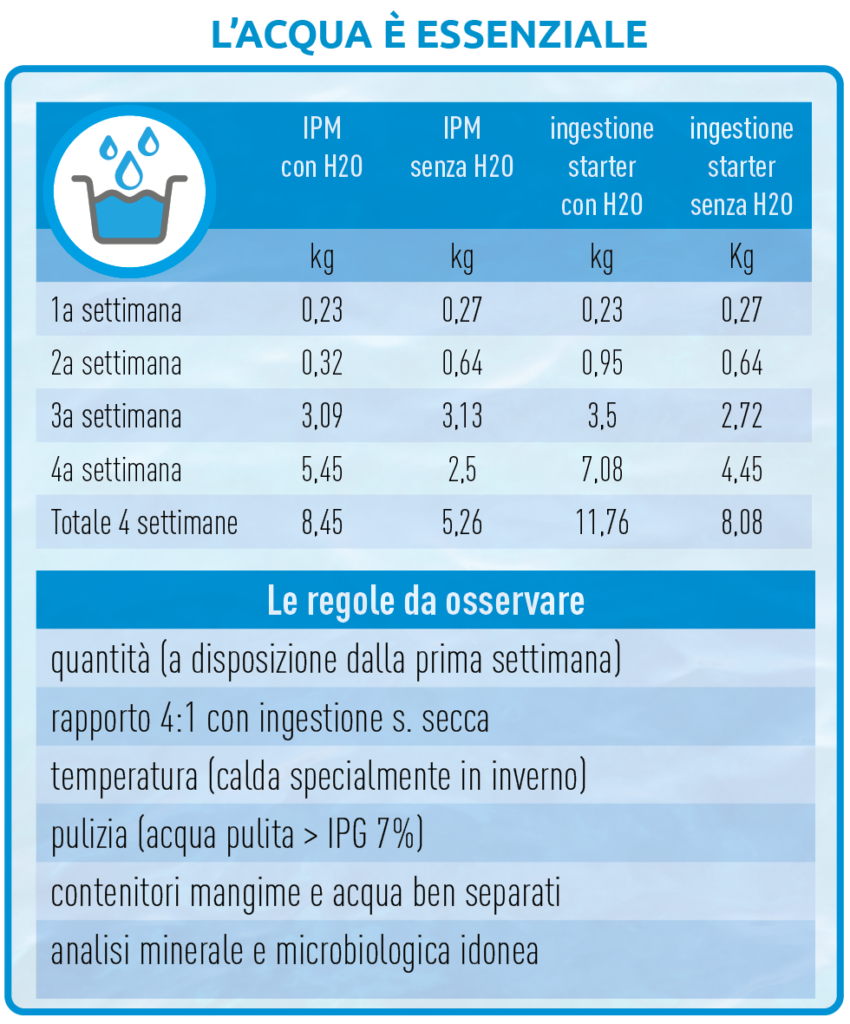

Fluid in the rumen

Rumen microorganisms require an adequate supply of water to sustain their vital activities. Bacterial growth and rumen development are intrinsically linked to water availability, which derives mainly from drinking water intake.

The benefits of providing calves with free access to water are well documented. Water availability from the earliest stages of life promotes increased body weight, improved starter intake, and a reduction in gastrointestinal disorders. The belief that milk alone provides sufficient water for calves is incorrect.

Rumen functionality

The rumen wall consists of two distinct layers: the epithelium and the muscle layer. Each component serves specific functions and develops in response to different stimuli.

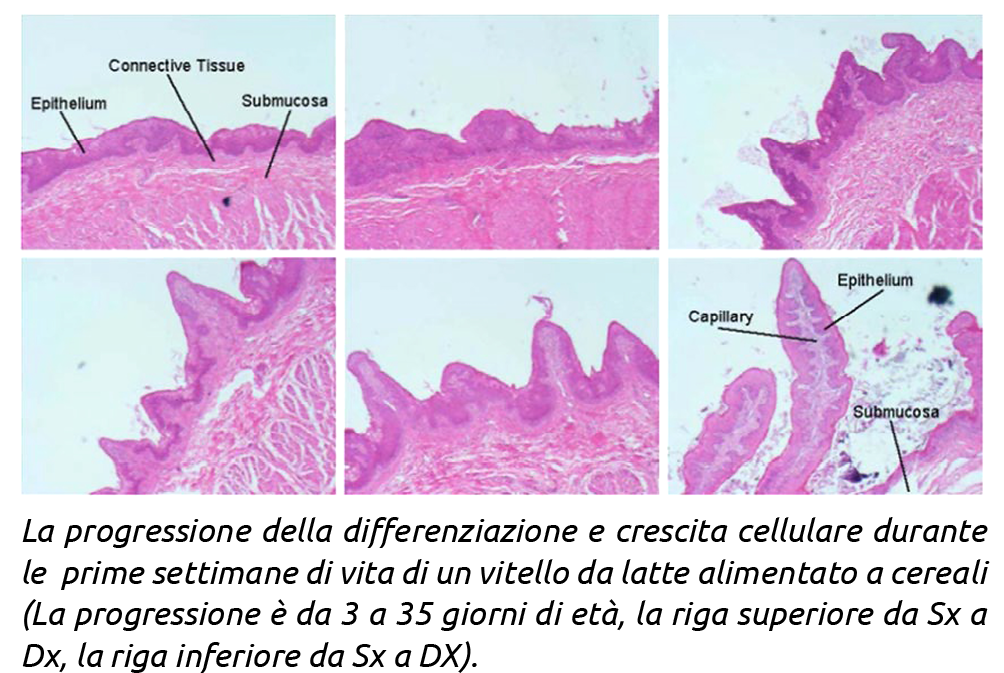

The epithelium forms the absorptive lining of the rumen and interfaces directly with rumen contents. This thin tissue layer is covered with numerous finger-like projections called papillae, which constitute the rumen’s absorptive surface.

The ruminal mucosa performs several key functions, including absorption, transport, metabolism of short-chain fatty acids, and protection of the rumen wall.

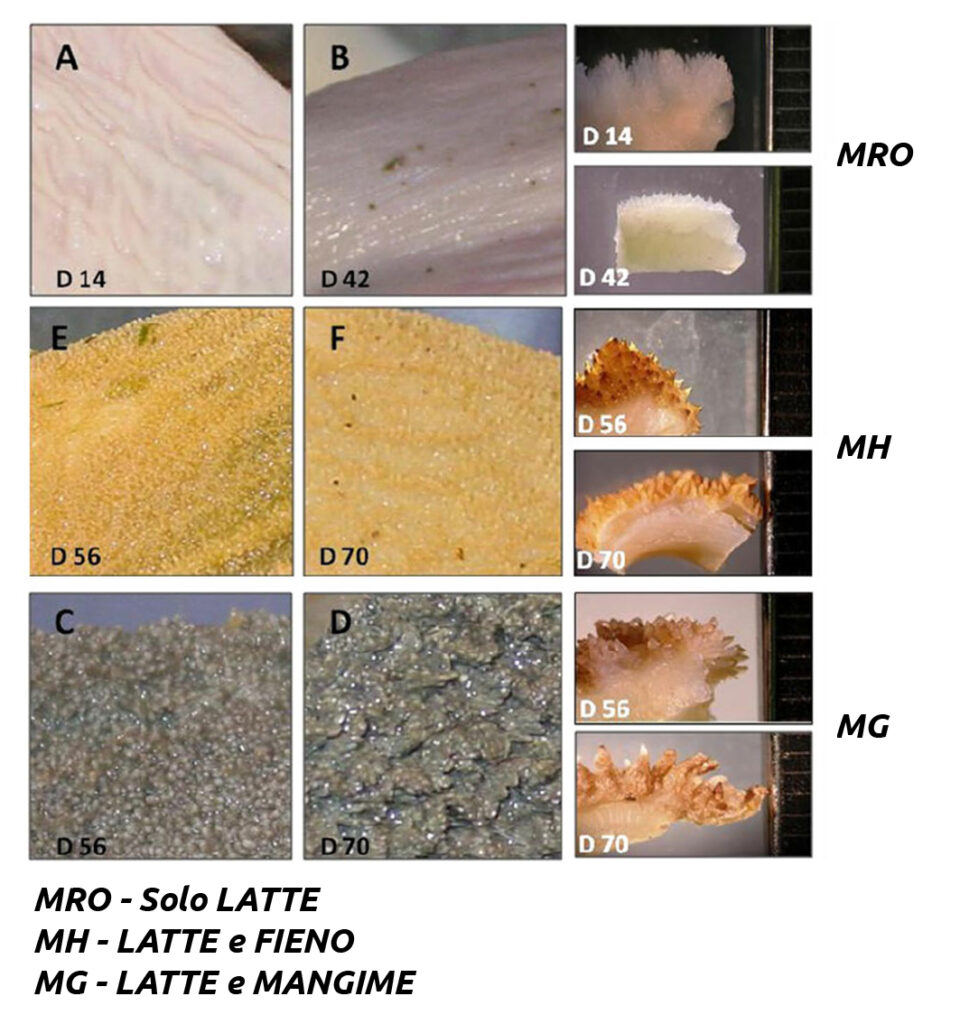

Proliferation and growth of the ruminal squamous epithelium promote increases in papilla length and width and thicken the internal rumen wall. Newborn calves have a smooth rumen floor with no prominent papillae. Calves fed exclusively on milk show limited rumen development, whereas increased solid feed intake accelerates ruminal fermentation, positively affecting rumen weight, papilla growth, degree of keratinization, and muscular development.

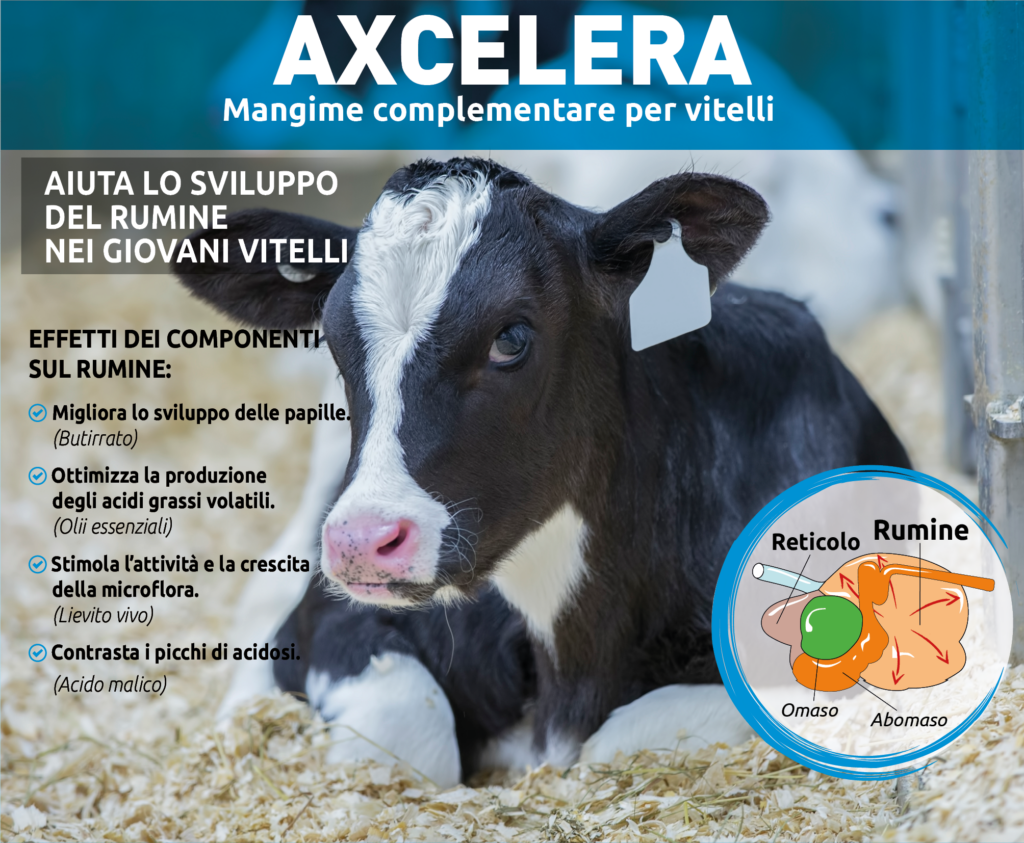

As calves consume more starter feed, ruminal digesta pH decreases and VFA concentrations gradually increase. The presence and absorption of VFAs provide essential chemical stimuli for ruminal epithelial proliferation. Papilla development is associated with increased blood flow through the rumen wall and with the direct effects of butyrate and propionate on gene expression.

Acetate-dominated fermentation, typically promoted by forages, has limited capacity to stimulate epithelial growth. Therefore, feeds used during weaning—milk, concentrates, and forages—each influence the rate and extent of ruminal epithelial development differently.

The second layer, the muscular layer, covers the external surface of the rumen and supports the internal epithelial layer. Its main function is muscle contraction, which facilitates mixing of rumen contents, regurgitation, and the transfer of digested material to the omasum.

Rumen musculature can be stimulated by feeds such as forages. When calves are fed a combination of milk, hay, and cereals shortly after birth, normal ruminal contractions can be observed as early as 3 weeks of age. Conversely, calves fed exclusively on milk may experience a prolonged delay in the onset of normal ruminal motility.

When starter feed and water are made available from the first days of life—even under so-called “intensive” milk-feeding programs characterized by high milk allowances during weaning—there is no negative interference with rumen development. On the contrary, when properly managed in terms of timing and quantities, this approach can act as an additional stimulus to rumen development. Epigenetic mechanisms likely play a fundamental role.

Starter feed and rumen development

Which physical form best promotes optimal rumen development?

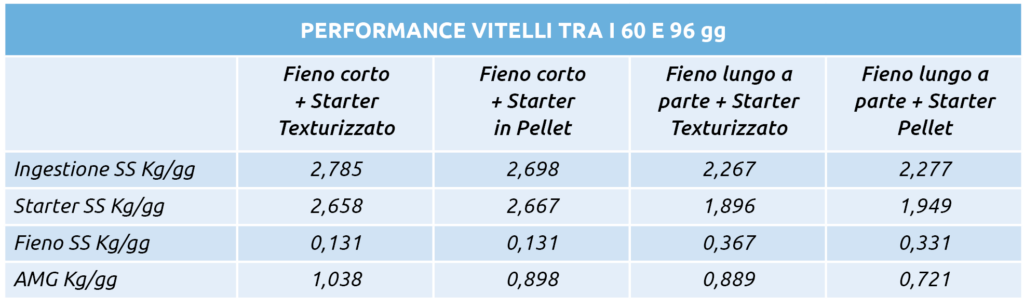

The availability and intake of calf starter feed are essential for calves during the pre-weaning period. Among protein sources, soybean meal has shown the most consistent results. Among cereals, maize is the most commonly used ingredient in calf starters, in its various forms (whole grain, meal, flaked, extruded). Other ingredients used as carbohydrate sources—such as cane molasses or sugar beet molasses—increase palatability, reduce particle separation, and decrease dustiness.

However, it has been demonstrated that a high molasses concentration reduces dry matter intake (DMI), may cause palatability issues, reduce growth, and increase the incidence of diarrhea.

To improve energy supply, the starter can also be supplemented with lipid sources, but only in minimal amounts to avoid depressing intake. In addition, a high-quality starter feed should contain a source of easily digestible fiber to prevent parakeratosis, or the accumulation of dead cells on rumen papillae that can impair nutrient absorption.

Recent studies have shown that supplementing starter feed with finely ground forage improves intake, growth, and ration digestibility. Feeds containing structured fiber stimulate saliva production during chewing and rumination; saliva provides urea and minerals, such as sodium bicarbonate, which help maintain normal rumen microbial growth and development. Coarse forages are important to promote growth of the rumen muscular layer and to maintain epithelial health.

Physical form of the starter feed

Calf interest in feed is influenced by several factors: odor, taste, and physical form.

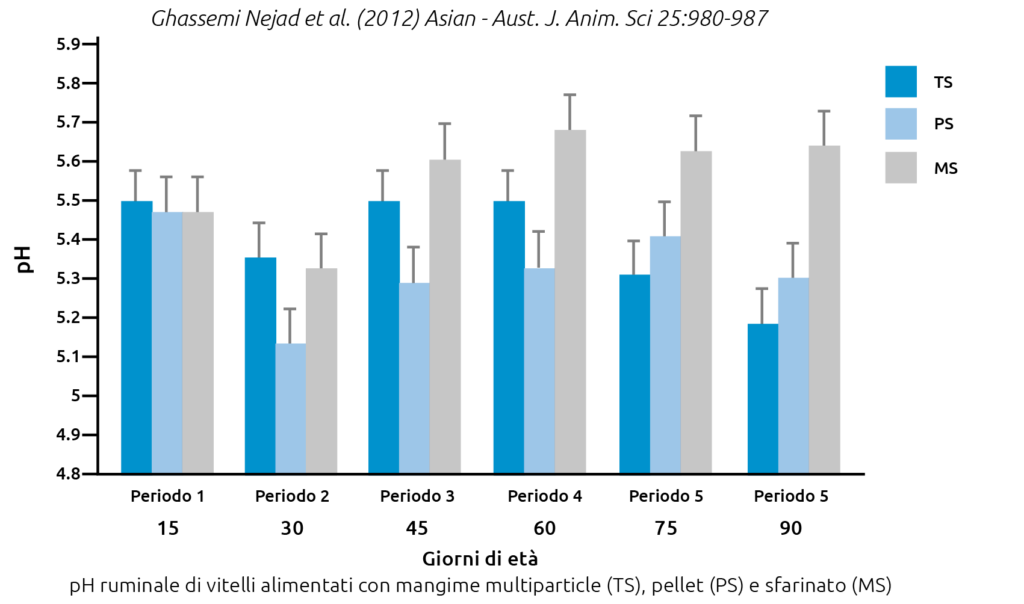

Regarding physical form, pellets have been shown to yield better results than mash. The debate remains open when comparing pellets with so-called “multiparticle” starters, in which most ingredients are visually distinguishable and have variable particle size. The latter are showing particularly interesting results in terms of intake and growth, and especially in stimulating rumen development, papillae growth, volatile fatty acid (VFA) profiles, and rumen pH.

The practice of introducing forage during weaning was long discouraged due to its low energy value and its tendency to shift fermentation toward acetate, thereby limiting papillae development. However, feeding diets low in fiber and rich in rapidly fermentable cereals can lead to a drop in rumen pH and reduced rumen motility, which may cause hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis of the ruminal epithelium.

Discover Tecnozoo solutions

Multiparticle Starter