Mycotoxins and hoof disorders in cattle: attention to feed hygiene

Climate variations in recent years, combined with current cultivation, harvesting, storage, and feed delivery techniques, have led to an increasing frequency of contamination of silages, cereals, and their by-products by fungi—particularly of the genera Aspergillus spp. and, even more so, Fusarium spp. The latter are producers of a wide range of mycotoxins, some of which are still poorly characterized but highly harmful to cattle.

The clinical pictures observed in the field are multifaceted, although they are often characterized by some easily recognizable signs for farmers, such as infertility, digestive metabolic disorders, increased risk of enterotoxemia, orchitis, agitation, tail necrosis, hemorrhagic diarrhea, as well as limb inflammation and hoof disorders.

It is possible—and indeed necessary, especially in particular years or specific periods of the year—to prevent the problem through interventions both on feeding management and through the use of products with proven efficacy

(Informatore Zootecnico, Carlo Angelo Sgoifo Rossi, Riccardo Compiani, Gianluca Baldi – March 10, 2015).

What are mycotoxins?

Mycotoxins are toxic substances (for other forms of life) with low molecular weight, naturally produced as secondary metabolites by filamentous microscopic fungi (molds). These fungi develop under specific environmental conditions, both in the field and during harvesting and storage of cereals, forages, and other feeds, whether single ingredients or compound feeds.

Some feeds are more susceptible than others to fungal growth. Mycotoxins exhibit great chemical variability and can induce acute and/or chronic toxicity in both animals and humans.

Among the various groups of mycotoxins, the only common feature—besides being produced by molds—is their strong resistance to high temperatures, chemical treatments, and subsequent feed preservation and processing. Mycotoxins do not elicit an immune response, and their effects may be neurotoxic, nephrotoxic, hepatotoxic, dermatotoxic, enterotoxic, as well as immunosuppressive, carcinogenic, and teratogenic.

The classification of mycotoxins and the molds that produce them is extensive and continuously evolving, due to the ongoing discovery of new mycotoxins or new effects of those already known. However, for practical purposes, it is useful to distinguish molds primarily based on where they develop: field molds or storage molds.

Field molds develop under conditions of high humidity (>70%) and large temperature fluctuations (warm days followed by cold nights).

Storage molds develop rapidly in forages after harvesting and in storage sites for cereals, oilseeds, and feeds with moisture content exceeding 15% for prolonged periods.

The presence of oxygen (molds are obligate aerobes, although they can grow at very low oxygen concentrations, ≈4%, i.e., microaerophilic environments), high moisture, and insufficient acidification of silage masses promotes mold growth.Absorption of mycotoxins occurs mainly through the digestive tract, after which each toxin exerts its specific mechanism of action.

In ruminants, the ruminal environment represents a barrier capable of inactivating a significant proportion of mycotoxins, making ruminants more tolerant to concentrations that would be intolerable for monogastric animals. In most cases, ruminal detoxification generates metabolites that are less toxic than the parent mycotoxin. However, in some cases, metabolites can be more toxic (e.g., zearalenone → α-zearalenol).

Detoxification capacity, largely driven by ruminal protozoa, varies according to the class of mycotoxins and the contribution of other microorganisms and bacteria, whose role is often underestimated. Some ruminal bacterial strains are indeed capable of degrading certain mycotoxins.

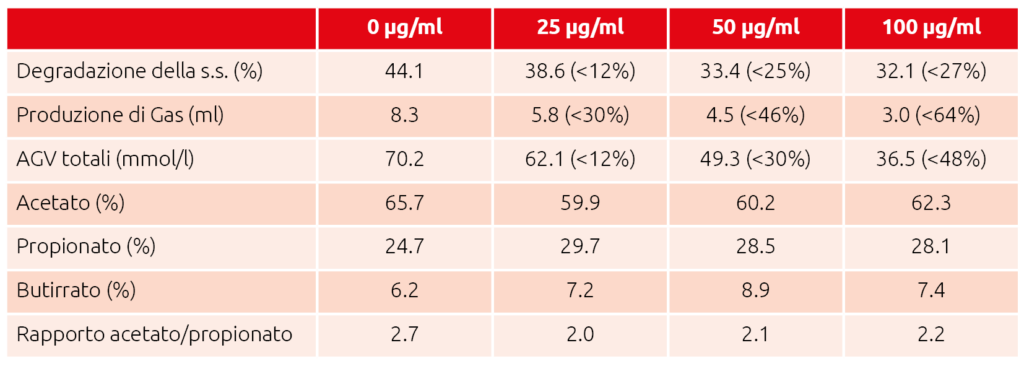

Table 1

Table 1

Effect of different patulin concentrations on in vitro ruminal fermentations¹⁰.

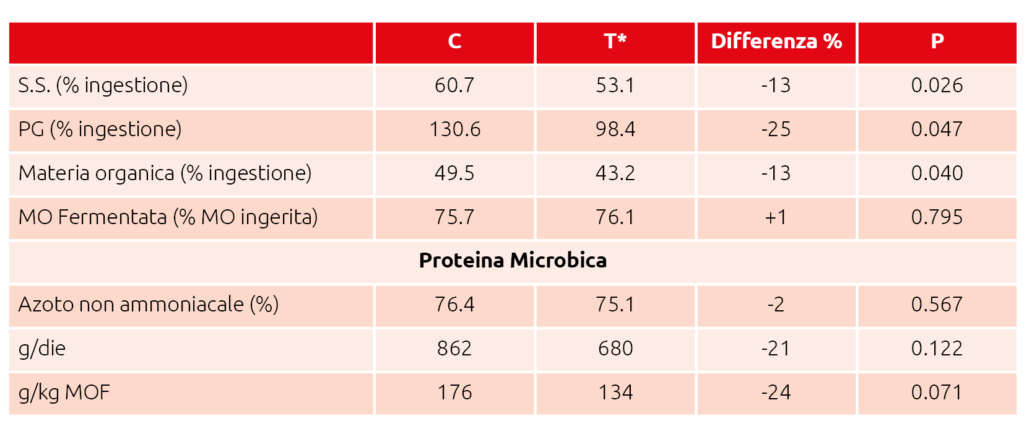

Table 2

Transfer of nutrients to the intestine in cows fed wheat contaminated with Fusarium spp. toxins¹¹.

T: diet containing wheat contaminated with DON 7.15 ppm and ZEA 186 ppb.

The rumen’s detoxification capacity is saturable and influenced by several concurrent factors, such as ruminal pH, diet composition, dietary changes, and metabolic disorders.

At the same time, many mycotoxins exert antimicrobial, antiprotozoal, and antifungal activity against ruminal microflora. Consequently, key indicators of good ruminal function—such as dry matter degradability, gas production, volatile fatty acid (VFA) synthesis, and microbial protein yield—are significantly impaired during mycotoxicosis, as shown in the studies reported in Tables 1 and 2 (C.A. Sgoifo Rossi et al., Large Animal Review, 2011).

Mycotoxins are therefore more likely to contribute to chronic rather than acute problems, such as increased disease incidence, suboptimal milk production, and impaired reproductive performance.

The most stressed cows—such as fresh cows—are particularly susceptible, often showing nonspecific and wide-ranging clinical signs.

Five principal mechanisms can be identified:

1. Reduction in dry matter intake.

2. Alteration of nutrient content, absorption, and metabolism in contaminated feeds.

3. Disruption of endocrine and exocrine systems.

4. Suppression of immune function.

5. Alteration of microbial growth.

The primary target organs are the liver and kidneys, with systemic consequences for immune function. Altered immune responses, combined with peripheral vasoconstriction, underlie the development of lesions that may also affect the hooves.

Ergot alkaloids (Claviceps purpurea)

Ergot alkaloids are mycotoxins produced by fungi of the genus Claviceps, specifically Claviceps purpurea, an ascomycete that parasitizes grasses—primarily rye, but also other cereals such as wheat, spelt, and oats. Claviceps purpurea is the most extensively studied species and is well known for its significant role in contaminating cereal-based feeds derived from infected crops.

This species produces, in infected plants, spur-like outgrowths called sclerotia—known in French as ergot—or, particularly in rye, horn-shaped protrusions. These are the fungal fruiting bodies and contain various toxic or psychoactive alkaloids belonging to the ergotine group, hence the name ergot alkaloids and the common term ergotism (or “horned rye”).

Environmental conditions that favor the development of Claviceps purpurea include humid weather, rainfall, and low temperatures, especially during cereal flowering in spring. After infecting the ovary, the fungus grows together with the developing kernels, forming sclerotia that are typically elongated compared to the grain and dark brown in color. (https://veterinariaalimenti.sanita.marche.it/Articoli/category/igienedegli-alimenti/micotossine-emergenti-gli-alcaloidi-dellergot)

Ergot alkaloids can induce severe vasoconstriction of small arteries. The body areas most commonly affected are the extremities—ears and tail in particular. This can result in lameness in ruminants and, in severe cases, inflammation of distal joints, loss of the hoof, or even gangrene.

Aflatoxins

These toxins have been associated with lameness, although their exact mechanisms of action are not yet fully understood.

DON, nivalenol, fumonisins, ochratoxins

These mycotoxins exert effects on skin and integuments, indirectly affecting the hooves.

HT-2 and T-2 toxins

Well known for their vasoconstrictive effects in mammals, these toxins may induce swelling or gangrene.

Due to their antibiotic-like effects, mycotoxins can cause death of ruminal bacteria and subsequent release of endotoxins (Baumgard et al., 2020), with both systemic and local effects.

In cases where there is a risk of mycotoxin presence in feedstuffs or rations, or when clinical signs are evident in the herd, it becomes necessary to supplement the diet with specific molecules capable of detoxifying mycotoxins, thereby preventing their absorption and systemic distribution.

Aflatoxin issues in maize

Mycotoxin contamination of food and feed is a global problem affecting both developed and developing countries. In animal production, mycotoxins primarily reduce productive efficiency and are often associated with deterioration of overall herd condition, leading to increased need for pharmaceutical interventions.

The widespread presence of aflatoxins in maize crops deserves particular attention, as more than 90% of maize production is destined for animal feeding.

[…] Among the most commonly used methods to reduce the negative effects of mycotoxin ingestion—especially in pig production—is the use of adsorbent agents. Recent studies conducted at ISAN evaluated the aflatoxin-binding efficiency of different adsorbents under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. Results showed that several bentonites (Ca-, Mg-, and Na-bentonite) and clinoptilolite were highly effective in binding aflatoxins. Other commonly used products (zeolites, kaolinites, and yeast cell walls) were less effective.Therefore, the correct selection of the adsorbent is critical to minimize the negative effects of mycotoxin ingestion, even at low dietary concentrations. Nutritional strategies aimed at increasing tolerance to certain mycotoxins—such as the use of compounds with antioxidant function—should also not be overlooked.