Autumn syndrome in the dairy cow

What happens after summer?

Analysis of the main issues observed in late summer and autumn.

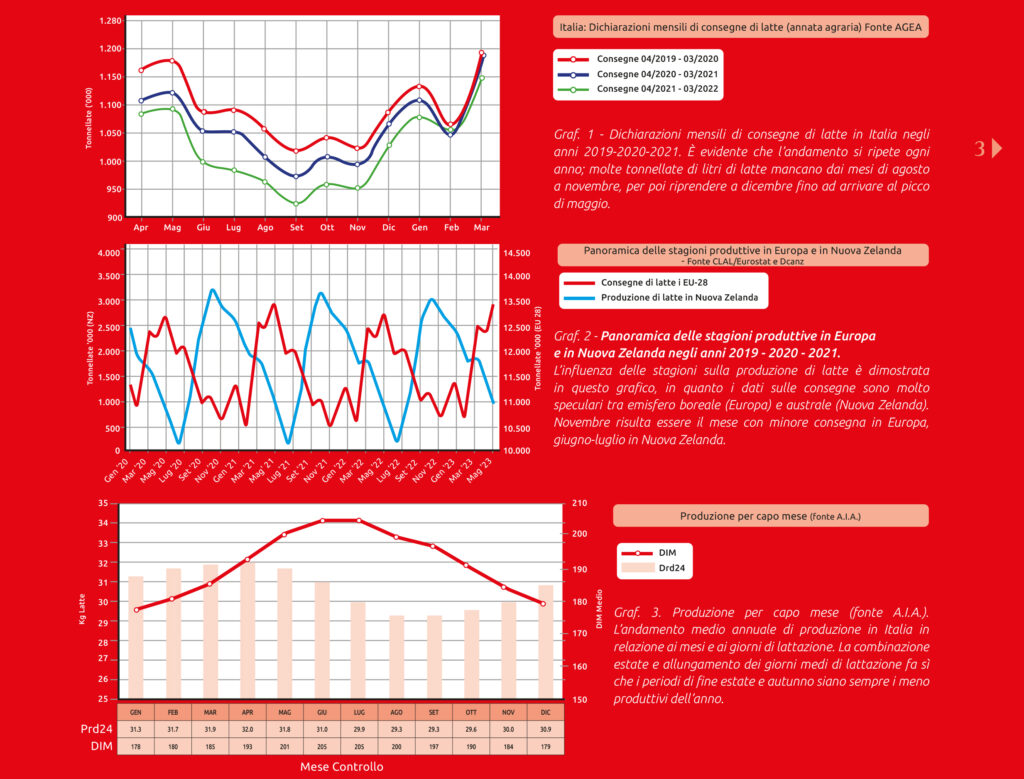

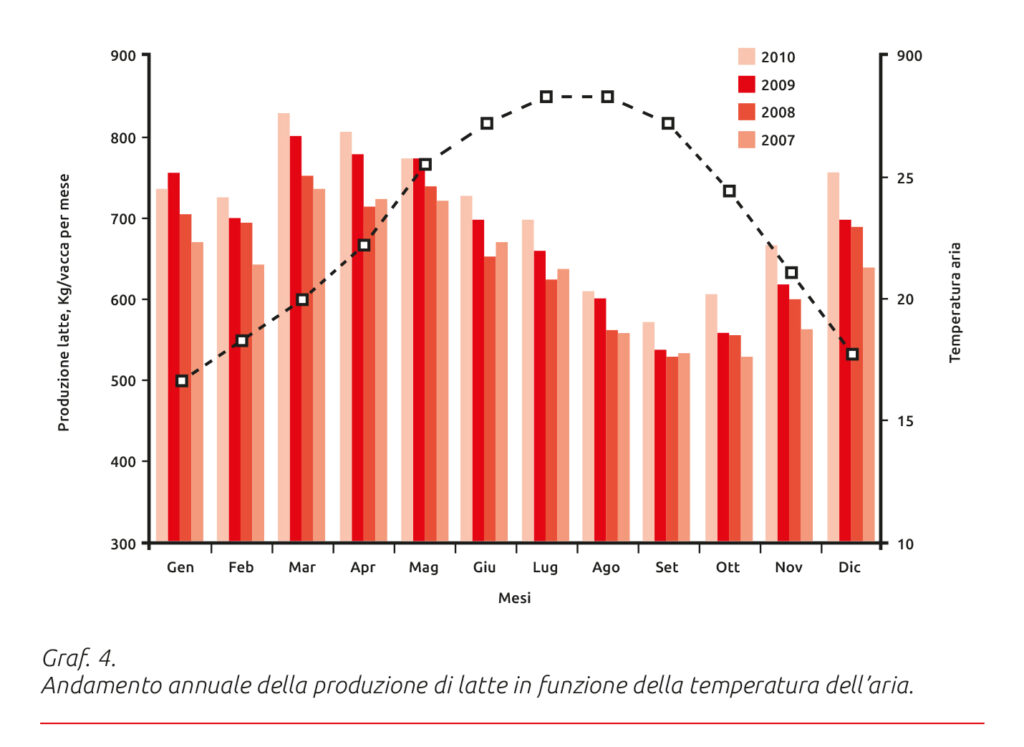

It is well known that the slowdown in production and the decrease in milk yield during the summer months are the result of a combination of unfavorable environmental conditions (heat and humidity) and the lengthening of average days in milk (graph 3).

Consequently, one might expect an increase in production as soon as temperatures begin to drop again, i.e. between late August and September. But this does not happen!

We therefore evaluate the various aspects of what can be defined as the autumn syndrome of the dairy cow.

By analyzing the graphs related to the Italian situation (graphs 1 and 3), it is evident that the months of August, September, October, and November are those with the lowest production. The opposite trend is observed in the Southern Hemisphere (particularly when extrapolating milk delivery data from New Zealand), where these are the most productive months of the year (graph 2).

There are therefore several factors affecting the lack of milk production: heat stress, photoperiod, replacement management, and the presence of fresh cows. In this article we will analyze the first two conditions.

Heat stress

By definition, heat stress can be described as the set of forces related to high temperatures that induce changes in the animal at different levels (from subcellular to macroscopic); these help the animal adapt to physiological alterations.

As documented in numerous studies worldwide, the effect of high temperatures on both dairy and beef cattle causes significant economic losses.

As is now well known, to determine heat stress conditions a formula is used (found in all animal science textbooks) that relates two specific parameters: temperature and humidity:

Since the 1980s, it was believed that a dairy cow entered heat stress at a THI of 72 (for example, THI 72 = 27°C and 30% humidity).

Today, however, with genetic improvement having made enormous progress—allowing the farming of highly productive and very efficient animals—it no longer makes sense to set this limit at 72.

Based on current knowledge, it is much more appropriate to set the threshold at a THI of 68, which translates to: 22°C and 50% humidity.

From a metabolic point of view during high summer temperatures…

the dairy cow attempts to dissipate as much heat as possible; one of the physiological strategies it can adopt is peripheral vasodilation. This promotes greater blood flow to the external areas and therefore greater heat dissipation.

Baumgard, from Iowa State University, demonstrated that an increase in peripheral vasodilation corresponds to a phenomenon of vasoconstriction at the intestinal level, with villus contraction and a reduced capacity to absorb nutrients.

This reduced blood flow at the visceral level leads to poor oxygen availability and therefore to an alteration of the integrity of the intestinal absorptive surface. The same research also highlighted that the reduced milk production is due for 50% to the loss of voluntary intake, and for the other 50% to the effect of heat stress on histological modifications of the intestine.

During heat stress, the reduced dry matter intake, combined with the loss of rumen buffering capacity, increases the risk of acidosis.

The association between reduced blood flow to the enteric system and ruminal and intestinal acidosis extends the condition of digestive strain, including an increase in oxidative stress.

The latter induces an imbalance between the production and removal of peroxides and free radicals, causing cell death and tissue damage.

Under heat stress conditions, even at the ruminal level the bacterial flora loses efficiency, with a worsening of microbial protein synthesis, fiber digestion, and biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids, resulting in a decrease in milk quality.

All these issues, in addition to worsening productive performance, also have a negative impact on cow condition.

In this situation, the administration of antioxidant substances has shown positive results; by neutralizing free radicals, they improve the animal’s metabolic status and normal rumen function.

Antioxidants, due to their ability to protect cells from the toxic and degenerative action of free radicals and peroxides, help restore normal oxidative balance in heat-stressed cows. This action also has a positive effect on dry matter intake during the summer period.

Discover the Normoterm line, ideal during the summer period:

Photoperiod

The photoperiod, i.e. the duration of daylight hours, has a significant influence on the behavior and milk production of dairy cows and plays a role in the autumn syndrome of the dairy cow.

The light or dark stimulus passes through the eyeball and, via the optic nerve, modifies the activity of the pineal gland (epiphysis). This gland acts as an internal clock, sensitive to the duration and intensity of light.

The pineal gland secretes melatonin, the hormone that regulates the sleep/wake cycle and influences the immune system, the reproductive system, and lactation.

Not all phases of a dairy cow’s life respond in the same way, however. Let us analyze the differences between the lactation and dry periods.

Lactation phase

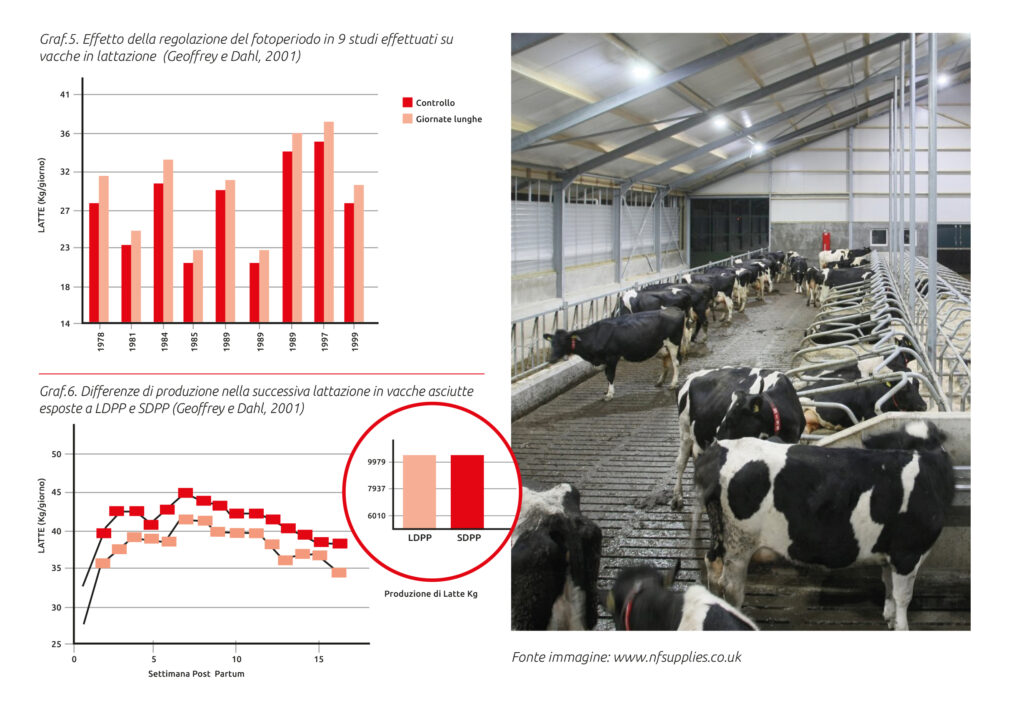

During lactation, the highest milk production occurs when daylight hours are increasing, particularly when light exposure exceeds 14 hours. In fact, exposure to light prevents melatonin secretion for most of the day and favors the secretion of prolactin and IGF-1, two hormones that influence mammary gland activity. Research has shown increased production in lactating cows exposed to a long photoperiod compared with animals under natural conditions.

Graph 5 (from Geoffrey and Dahl, 2001) summarizes 9 studies that recorded significant positive effects on production following constant exposure to 16 hours of light per day. With a positive photoperiod, metabolism and the immune system are also more efficient.

Dry period

Unlike lactating cows and heifers, the group of dry cows and prepartum heifers seems to achieve better results after exposure to a short photoperiod with only 8 hours of daily light (Miller et al., 2000).

Graph 6 (from Geoffrey and Dahl, 2001) shows the difference in production in the subsequent lactation of two groups of dry cows (with equivalent production in the previous lactation) exposed to LDPP – long-day photoperiod with 16 hours of light and 8 hours of darkness per day – (line with pink squares) and SDPP – short-day photoperiod with 8 hours of light and 16 hours of darkness per day – (line with red squares).

Exposure for 2–3 weeks in the prepartum period to a short photoperiod for these animals appears to act as a sort of reset of their ability to respond to exposure to a greater number of daylight hours after calving.

In conclusion, through manipulation of the photoperiod—therefore of the duration of light exposure of lactating cows—it is reasonable to obtain benefits in terms of milk production, fertility, growth, and efficiency of the immune system.

To stay up to date with Tecnozoo news, follow us Instagram or on Facebook.