Heat stress in dairy cows, download the 2022 magazine!

What strategies can be implemented to maintain their thermal neutrality?

Heat stress in dairy cows has a major impact during periods of extreme heat.

Physiologically, however, animals have two ways to adapt to heat peaks.

To cope with heat waves, dairy cows can naturally regulate their body temperature in two ways:

1. Increasing heat dissipation through:

- Evaporation, by increasing subcutaneous blood flow, respiration rate, salivation, etc.

- These activities increase maintenance energy requirements by 20% at 35 °C.

- This means that part of the energy normally destined for production is diverted to thermoregulation.

2. Reducing heat production

- By reducing overall activity and changing feeding patterns. (Heat production in cows is mainly due to ruminal fermentations; for this reason, cows will reduce dry matter intake by 10–30%).

- Dry matter intake will decrease, as will milk production.

Is a reduction (even a significant one) in dry matter intake sufficient to explain the reduced productivity observed during heat stress?

No. A more accurate understanding of the biological reasons why stress reduces productive performance allows us to better understand how to alleviate it.

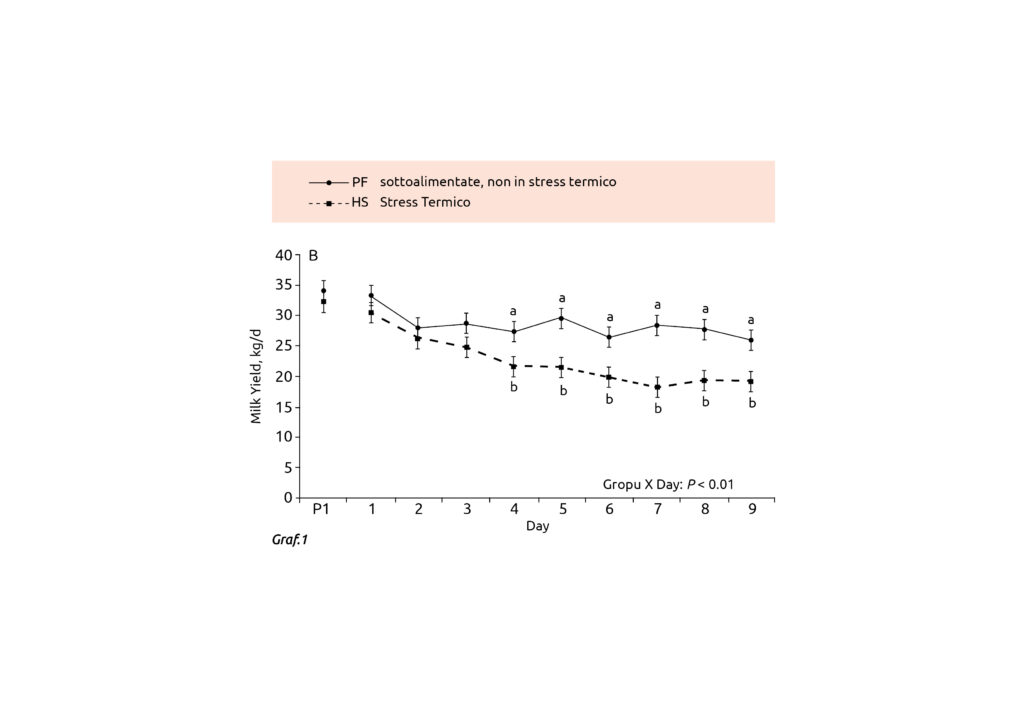

As demonstrated by studies by Rhoads et al., 2009; Wheelock et al., 2010; and Baumgard et al., 2012, during heat stress dairy cows lose much more milk (about 45%) compared to cows not under heat stress but underfed with the same amount of dry matter (about 19%). Consequently, reduced dry matter intake accounts for only part—around 50%—of the causes of reduced milk production.

The remaining 50% is attributable to metabolic changes induced by heat stress in the animal.

Despite negative energy balance and weight loss, adipose tissue is not mobilized (unlike what can occur during transition and at calving).

Indeed, severe heat stress in dairy cows induces profound changes both in nutrient partitioning (nutrients are no longer directed toward milk production but toward defense against heat) and at the endocrine level, with significant increases in epinephrine, norepinephrine, and especially cortisol.

Cortisol levels during periods of heat stress can be up to 10 times higher than normal, leading to several important issues, including health-related ones:

- Cortisol reduces protein synthesis and inhibits oxytocin release (with consequent difficulties during milking);

- Cortisol limits white blood cell function and replication, reducing protection against potential infections;

- High cortisol levels can also cause failure or delay of ovulation, reducing animal fertility.

Heat stress in dairy cows: how can the lack of NEFA be explained?

As already mentioned, although heat stress in dairy cows implies a significant reduction in dry matter intake and weight loss, it does not promote mobilization of adipose tissues.

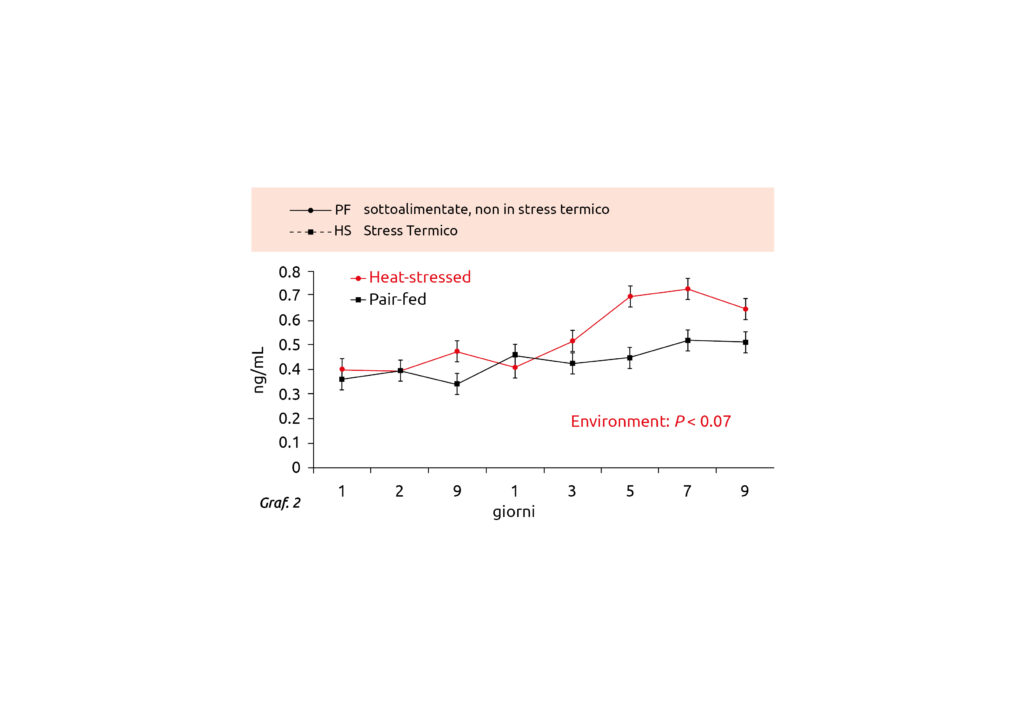

The unusual lack of NEFA in heat-stressed dairy cows is partly explained by high circulating insulin levels, as insulin is a powerful anti-lipolytic hormone.

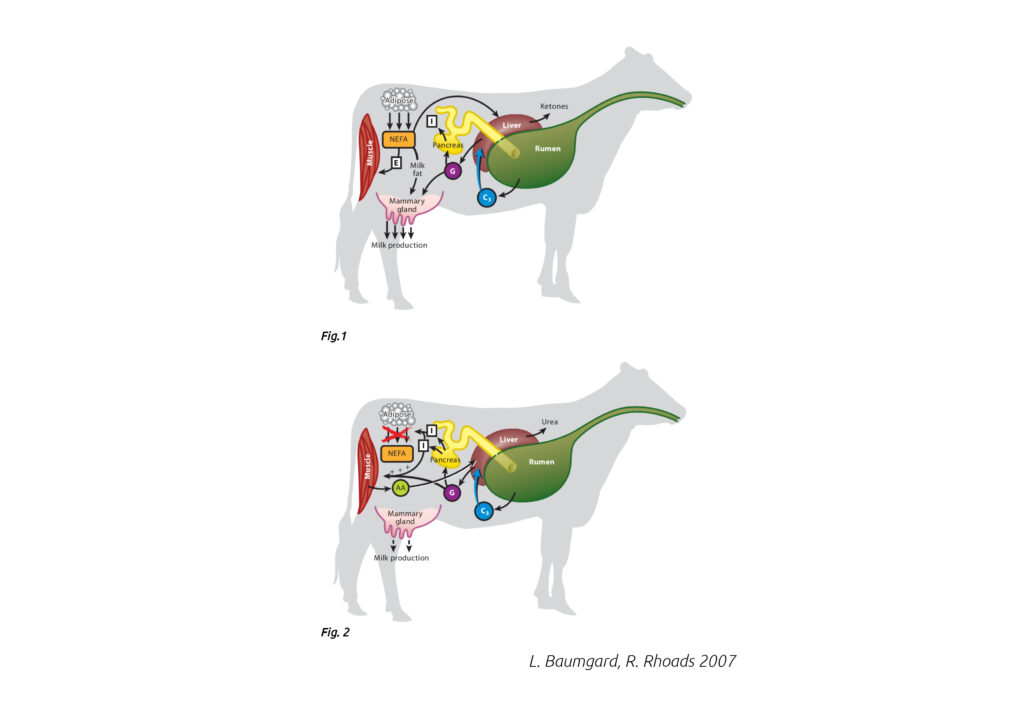

As shown in Figure 1, under conditions of underfeeding but not heat stress, there is normal ruminal production of propionic acid, which reaches the liver and is converted into glucose. This glucose then reaches the pancreas, stimulating moderate insulin production;

much of the glucose is instead directed to the mammary gland for milk production.

There is also normal mobilization of adipose tissue with the release of NEFA, destined to return to the liver for glucose production, increase milk fat content, and provide energy to muscle tissue.

In a situation of heat stress in dairy cows (Figure 2), ruminal activity decreases, resulting in limited production of propionic acid and consequently less glucose produced by the liver.

Part of this glucose goes to the pancreas and part to the muscles rather than to the mammary gland (this is the major productive difference).

Furthermore, high insulin production inhibits fat mobilization, resulting in a reduction of fat in the mammary gland (and in milk). At the muscle level, it promotes mobilization of “glucogenic” amino acids, increasing circulating urea levels.

To summarize, heat stress in dairy cows leads to:

1. High insulin levels

2. Reduced NEFA levels

3. Glucose being redirected to muscle tissue

As a result, animals require more energy, especially in the form of glucose.

Supplementation with hexose sugars such as sucrose, dextrose, fructose, or glycerol (even though it is an alcohol) becomes a valuable support during this delicate period of the year to help cope with heat stress in dairy cows.

Sugars contained in forages are not always sufficient, as they are mainly pentoses, which are poorly digestible (no more than 50%).

To discover all the products for dairy cows and to cope with heat stress, visit the dedicated section on our website:

Stay up to date with all Tecnozoo news! Follow us on Facebook and Instagram.